Actus Reus and Mens Rea: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Fr|Actus_Reus_et_Mens_Rea}} | |||

{{Currency2|January|2016}} | {{Currency2|January|2016}} | ||

{{LevelZero}} | {{LevelZero}} | ||

Revision as of 16:41, 6 June 2024

| This page was last substantively updated or reviewed January 2016. (Rev. # 93694) |

- < Criminal Law

- < Proof of Elements

General Principles

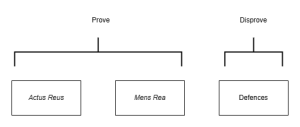

In a criminal trial, the Crown will present evidence that will tend to establish the offence for which the accused is charged.[1] Each offence in the Criminal Code is broken down into "elements" that are to be proven.[2] Each element that is considered "essential" must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt before a judge can return a guilty verdict.[3]

In addition to the "essential elements" the Crown must also disprove all elements of any legal defence beyond a reasonable doubt where there is an "air of reality" to the defence.[4]

The elements of a particular offence are derived from the explicit wording of the offence and are implied by the judicial interpretation of the offence.

For a list of elements of major offences, see Offences by Category.

- Actus Reus and Mens Rea

Common with all criminal offences in Canada are the basic requirements that the Crown must prove there was an action or omission (known as the "actus reus") and that there was a simultaneous criminal intent (known as the "mens rea") within particular circumstance.[5]

What constitutes a actus reus and mens rea depends on the offence itself which is defined by federal legislation. [6]For example, a drug possession charge requires proving mens rea by establishing that the accused had knowledge of the presence of the substance on their person. An assault, however, requires proving mens rea by establishing an intention to apply force.

In a trial situation, it is fundamental that the Crown must prove the elements of the particularized charge as they are the charge and not simply the abstract definition of the offence as found in the Code.[7]

There are more static elements that need to be proven, such as the identity of the accused as the person subject to the offence, jurisdiction of the court over the person accused, and the timing of the offence. Identity can sometimes be a non-trivial issue where the accused was not caught in the act. Courts are very wary of wrongful convictions based on identity. [8] The jurisdiction and time elements simply establish that the court is able to adjudicate the matter. Judges cannot concern themselves of offences outside of the province or offences without any specific time period.[9]

- Defences

Where defences are concerned, the Crown has no obligation to disprove them unless the evidence provides an "air of reality" to the availability of a defence.

- ↑

see more at Role of the Crown

- ↑

sometimes referred to as the corpus delicti ("body of the offence")

- ↑ R v Graham, 1972 CanLII 172 (SCC), [1974] SCR 206

- ↑ Air of Reality

- ↑

R v Gillis, 2013 NBPC 3 (CanLII), per Lampert J, at para 84

R v Butt, 2012 CM 3006 (CanLII), per d'Auteuil, at para 29

- ↑ Section 8 of Criminal Code prohibits common law offences

- ↑ R v Saunders, 1990 CanLII 1131 (SCC), [1990] 1 SCR 1020, per McLachlin J, at para 5 ("It is a fundamental principle of criminal law that the offence, as particularized in the charge, must be proved.")

- ↑

see Identity

- ↑

see also Time and Place

Simultaneous Principle

The "simultaneous principle" requires that there be "an intersection of the act and fault requirements of the criminal offence in question."[1]

This "simultaneous principle" is not to be applied strictly. For example, it is not necessary that the mens rea form "at the inception of the actus reus."[2] There only needs to be some overlap at some moment in time.[3] Accordingly, an act may start off innocent and then become the basis of criminal liability once the mens rea is formed during the act.

For the purpose of considering the simultaneous principle, a series of acts may be considered a continuous transaction.[4]

- ↑ R v McCague, 2006 ONCJ 208 (CanLII), 209 CCC (3d) 557, per Trotter J

- ↑ R v Cooper, 1993 CanLII 147 (SCC), [1993] 1 SCR 146, per Cory J

- ↑ Cooper, ibid. ("There is, then, the classic rule that at some point the actus reus and the mens reas or intent must coincide")

- ↑

Cooper, ibid.

see also R v Paré, 1987 CanLII 1 (SCC), [1987] 2 SCR 618, per Wilson J

Actus Reus

The actus reus concerns the "external elements" of the offence.[1] It is an act or omission of the accused that is required for proof of the offence.[2]

Criminal law only punishes those acts which are conscious and voluntary.[3]

- Voluntariness

Fundamental to criminal liability is that the criminal act be voluntary as it reflects respect for a person's autonomy and only punishes those who have the capacity to conform with the law.[4] All actions are presumed to be voluntary.[5]

Reflexive actions of accused can be considered involuntary.[6]

- Omissions

An omission can make out an actus reus where there is a legal duty to act.[7]

- ↑ R v Leech, 1972 CanLII 242 (AB QB), 10 CCC (2d) 149, per Macdonald J, at para 18 ("actus reus means all the external ingredients of the crime") citing Williams, Criminal Law, 2nd ed

- ↑ see numerous references to "act or omission" within the code, referring to all "external ingredients" of the offence at issue

- ↑

R v Mathisen, 2008 ONCA 747 (CanLII), 239 CCC (3d) 63, per Laskin JA

- ↑ R v Luedecke, 2008 ONCA 716 (CanLII), 236 CCC (3d) 317, per Doherty JA, at para 56

- ↑ R v Stone, 1999 CanLII 688 (SCC), [1999] 2 SCR 290, per Bastarache J, at para 171

- ↑

R v Pirozzi, 1987 CanLII 6810 (ON CA), , 34 CCC (3d) 376, per curiam

R v Mullin, 1990 CanLII 2598 (PE SCAD), 56 CCC (3d) 476, per Carruthers CJ

R v Wolfe, 1974 CanLII 1643 (ON CA), 20 CCC (2d) 382, per Gale CJ: accused hits victim on head with telephone by reflex

- ↑ see Duty of Care

Circumstances of the Act or Omission

Certain offences only criminalize acts that occur only within certain circumstances. Where the circumstances in which the conduct takes place are an essential element to the offence these are referred to as the "attendant circumstances" or "external circumstances."[1]

A typical example of external circumstances is the required proof of lack of consent in assault-based offences such as sexual assault.[2]

- ↑ e.g. R v United States of America v Dynar, 1997 CanLII 359 (SCC), [1997] 2 SCR 462, per Iaccobucci J. uses the term "attendant circumstances"

- ↑ see Consent in Sexual Offences

Consequences of the Act or Omission

The code definition of the Offence will sometimes describe necessary consequences that must arise for the Offence to be complete. This requires the crown to prove that the consequence occurred and that the consequence was caused by the Accused's conduct.

Mens Rea

An offence cannot be complete without proof of the requisite blameworthy state of mind, also known as the "mens rea" of the offence.[1]

The requirement is not one that is fixed but will depend on the specifics of the offence.

It can be either on an "objective" or "subjective" standard.

The mens rea will apply not simply to the level of intention behind the accused's conduct but will also apply to their level of knowledge, depending on the offence. The subject of the knowledge will be either the knowledge of the circumstances in which the conduct occurs or knowledge of the consequences that result from the conduct.[2]

There are several available mens rea standards including negligence, knowledge, wilfulness, recklessness, general intent or specific intent.

The standard applicable for a given offence will be set by the wording and interpretation of the legislation.[3]

The mens rea required for an offence will be applied to three types of elements. Elements of conduct, circumstances, and consequence. The elements of conduct refers to the actus reus of the offence.

The mens rea does not require that the accused be aware that what they are doing is a crime. The maxim that "ignorance of the law is no excuse" exempts any requirement of such awareness.[4]

The mens rea does not include the proof of any "motive" for the commission of the offence.[5] But aspects such as motive will go towards the overall moral blameworthiness of the offence which in turn affects the penalty to be imposed.[6]

- Minimum Constitutional Level of Mens Rea

The principles of fundamental justice within s. 7 of the Charter "require proof of a subjective mens rea with respect to the prohibited act."[7] This because it is not appropriate for criminal law to punish the "morally innocent."[8]

- History

The original maxim of "mens rea" comes from the phrase "actus non facit rerun nisi mens sit rea."[9]

Traditionally, there is "no one such state of mind," mens rea refers only to the requirement that there must be a mental element that varies "according to the different nature of different crimes."[10]

The requirement of mens rea for criminal offences traces back to the 18th century where there must be a "vicious will" or "evil mind" for an unlawful act to be criminal. It was diluted over time to permit lesser mental states without motive or understanding of illegality.[11] Others referred to it as an "intention to commit a crime."[12]

- United Kingdom

Under the UK Criminal Justice Act 1967, s. 8, "criminal intent" is defined as:

- Proof of criminal intent.

A court or jury, in determining whether a person has committed an offence,—

- (a)shall not be bound in law to infer that he intended or foresaw a result of his actions by reason only of its being a natural and probable consequence of those actions; but

- (b)shall decide whether he did intend or foresee that result by reference to all the evidence, drawing such inferences from the evidence as appear proper in the circumstances.

– CJA

- ↑

R v Butt, 2012 CM 3006 (CanLII), per d'Auteuil , at para 29

R. v. Prince (1875), L.R. 2 C.C.R. 154; R. v. Tolson (1889), 23 Q.B.D. 168

R. v. Rees (1955), 115 C.C.C. 1, 4 D.L.R. (2d) 406, [1956] S.C.R. 640

Beaver v. The Queen (1957), 118 C.C.C. 129, [1957] S.C.R. 531, 26 C.R. 193

R. v. King (1962), 133 C.C.C. 1, 35 D.L.R. (2d) 386, [1962] S.C.R. 746

R v MacDonald, 1987 CanLII 9403 (NS SC), 79 NSR (2d) 215, at para 16 - ↑

Butt, ibid., at para 29

- ↑

Butt, ibid., at para 29

- ↑

see s. 19 of the Criminal Code

see also Defences for "ignorance of the law" principle

- ↑

Butt, supra, at para 29

- ↑ R v Bernard, 1988 CanLII 22 (SCC), [1988] 2 SCR 833, at para 78 ("those generally more serious offences where the mens rea must involve not only the intentional performance of the actus reus but, as well, the formation of further ulterior motives..."

- ↑ R v Vaillancourt, 1987 CanLII 2 (SCC), [1987] 2 SCR 636, per Lamer J, at p. 653

- ↑

Vaillancourt, ibid., at p. 653

- ↑

see James Stephen, History of the Criminal LAw of England (vol 2, pp. 94-5)

Rex v. Crowe, 1941 CanLII 297 (NS CA), 76 CCC 170, per Chisholm J - ↑ Crowe, ibid.

- ↑

R v Sault Ste. Marie, 1978 CanLII 11 (SCC), [1978] 2 SCR 1299, 40 C.C.C. (2d) 353 at pp. 357-8 (CCC)

Blackstone Commentaries, 4 Comm. 21 ( "to constitute a crime against human law, there must be first a vicious will, and secondly, an unlawful act consequent upon such vicious will")

see also R v Tolson, (1889), 23 QBD 168

Stephen, History of Criminal Law of England, 1993, II - ↑ see Bouvier