Electronic Documents and Records: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m Text replacement - "\{\{fr\|([^\}\}]+)\}\}" to "fr:$1" |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[fr:Documents_et_dossiers_électroniques]] | |||

{{Currency2|January|2024}} | {{Currency2|January|2024}} | ||

{{LevelZero}} | {{LevelZero}} | ||

Revision as of 14:26, 14 July 2024

| This page was last substantively updated or reviewed January 2024. (Rev. # 95408) |

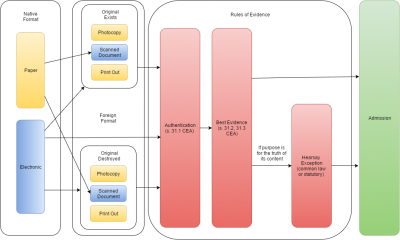

Introduction

The admission of electronic documents are governed by s.31.1 to 31.8 of the CEA in addition to traditional rules of admissibility. The provisions are meant to apply "in conjunction with either some common law general rule of admissibility of documents or some other statutory provision". The sections have the effect of deeming electronically produced documents as "best evidence" (see s.31.1 and 31.2).[1]

The CEA must be complied with for all evidence coming from a computer.[2]

In determining the admissibility of electronic documents the court must determine whether the record is authentic and reliable.[3]

The regime set out in s. 31.1 to 31.8 is meant to give a "functional approach" to the admission of electronic records.[4]

There is some suggestion that a functional approach will take into account the practicalities of alternative methods of proof.[5]

The CEA provision are simply a codification of common law rules for electronic records.[6]

- Rigorous Scrutiny of Reliability and Malleabillity of Electronic Records

Judges are expected to engage in "rigorous...evaluation" of electronic evidence in terms of reliability and probative value.[7]

The fact that records are electronic render them more malleable and so should be considered more closely for authenticity and reliability.[8]

- Evidence Act Only Affects Authentication and Best Evidence

These rules, however, are not intended to "not affect any rule of law relating to the admissibility of evidence, except the rules relating to authentication and best evidence."[9]

These provisions are meant to address the fact that "technological change has rendered the former distinction between originals and copies a moot distraction in many areas."[10]

It has been suggested that s. 31 is not designed as an exception to hearsay, instead only provide a process of authentication and admissibility.[11]

In most cases where electronic documents are being tendered as documentary evidence—ie. where the data was inputted by a human—it should be treated as hearsay.[12]

In order to admit electronic documents for the truth of its contents, in the absence of the author, may only be admitted as business records through s. 30 of the CEA or by using one of the hearsay exceptions.[13]

- Records of Automated Processes

Records created by an automated process is not hearsay as there is no person behind the records that could potentially be cross-examined on the meaning of the information.[14]

- Variable Standard

The admission of electronic documents will vary on the format that the record takes (printout, scanned copy, or native digital format). All cases the documents must be authentic and satisfy the best evidence rule.

- Appeals

In certain cases, non-compliance with the CEA can amount to a miscarriage of justice.[15]

- ↑

R v Morgan, [2002] NJ No 15 (Prov. Ct.)(*no CanLII links)

, per Flynn J, at paras 20-21

R v Oland, 2015 NBQB 245 (CanLII), 1168 APR 224, per Walsh J, at para 53

see also David M. Paciocco, "Proof and Progress" 11 CJLT 2 (2013) at p. 193 ("To be lear, subsections 31.1 to 31.8 do not authorize the ultimate admission of electronic documentary evidence. These provisions deal solely with issues concerning the integrity of the document being offered as proof, not with the admissibility of the document's contents.") - ↑ R v Donaldson, 140 WCB (2d) 513(*no CanLII links) , per Paciocco J, at para 3

- ↑ R v Nde Soh, 2014 NBQB 20 (CanLII), 1079 APR 328, per Lavigne J, at para 22 (“In my view, this is a voir dire dealing with evidential principles within the context of an electronic world. The Court must decide whether the authenticity and reliability of the electronic documents has been proven.”)

- ↑

R v Ball, 2019 BCCA 32 (CanLII), 371 CCC (3d) 381, per Dickson JA, at paras 52, to 76 75 to 76, 80

- ↑

e.g. R v Bernard, 2016 NSSC 358 (CanLII), per Gogan J

Ball, supra, at para 79

- ↑

R v Martin, 2021 NLCA 1 (CanLII), per Hoegg JA, at para 30

R v Hirsch, 2017 SKCA 14 (CanLII), per Caldwell JA, at para 18

R v CB, 2019 ONCA 380 (CanLII), 376 CCC (3d) 393, per Watt JA, at para 57 - ↑ R v Aslami, 2021 ONCA 249 (CanLII), per Nordheimer JA, at para 30

- ↑ Soh, ibid. ("electronic documents are much more malleable than ordinary documents. They give rise to specific problems with respect to authenticity and reliability. It is possible to overcome these problems by applying sections 31.1 to 31.8 of the Act.") see also R v Andalib-Goortani, 2014 ONSC 4690 (CanLII), 13 CR (7th) 128, per Trotter J

- ↑ See s. 31.7 ("31.7 Sections 31.1 to 31.4 do not affect any rule of law relating to the admissibility of evidence, except the rules relating to authentication and best evidence.") 2000, c. 5, s. 56.

- ↑

R v Hall, 1998 CanLII 3955 (BC SC), [1998] BCJ No 2515, per Owen-Flood J, at para 52

See also Desgagne v Yuen et al, 2006 BCSC 955 (CanLII), 33 CPC (6th) 317, per Myers J suggesting file copies are sufficient for litigation unless integrity is being challenged

- ↑

R v Mondor, 2014 ONCJ 135 (CanLII), per Greene J, at para 38

- ↑

Mondor, ibid., at paras 18 to 19

Underwood and Penner, Electronic Evidence in Canada (Toronto: Carwell, 2013), at pp. 13, 14

- ↑

Mondor, ibid., at para 38

- ↑

Saturley v CIBC World Markets, 2012 NSSC 226 (CanLII), 1003 APR 388, per Wood J

- ↑ Ball, supra, at paras 87 to 88

Definition of Electronic Documents

Under s. 31.8 of the CEA, "electronic documents" are defined as:

31.8 The definitions in this section apply in sections 31.1 to 31.6 [electronic records].

...

"electronic document" means data that is recorded or stored on any medium in or by a computer system or other similar device and that can be read or perceived by a person or a computer system or other similar device. It includes a display, printout or other output of that data.

...

2000, c. 5, s. 56.

This definition would include emails and all other electronic communications, all computer files, meta data associated with computer files, content of websites such as Facebook, Twitter, and chat logs found online.[1]

Similarly, s. 841 of the Code defines "data" and "electronic document" as they apply to s. 842 to 847 of the Code:

- Electronic Documents

- Definitions

841 The definitions in this section apply in this section and in sections 842 to 847 [misc provisions re electronic docs].

"data" means representations of information or concepts, in any form. (données)

"electronic document" means data that is recorded or stored on any medium in or by a computer system or other similar device and that can be read or perceived by a person or a computer system or other similar device. It includes a display, print-out or other output of the data and any document, record, order, exhibit, notice or form that contains the data. (document électronique)

R.S., 1985, c. C-46, s. 841; R.S., 1985, c. 31 (4th Supp.), s. 97; 2002, c. 13, s. 84.

[annotation(s) added]

- Examples

Courts have found that the following records fit within the meaning of "electronic documents":

- audio recording made on a cellphone[2]

- emails[3]

- Facebook messages[4]

- cellphone text messages[5], including messages sourced from the teleco company[6]

- 911 audio recording[7]

- printouts from government databases[8]

- photographs of a chat on a phone[9]

- pharmacy prescription receipts[10]

- ↑

R v Nde Soh, 2014 NBQB 20 (CanLII), 1079 APR 328, per Lavigne J, at para 21

Desgagne v Yuen et al, 2006 BCSC 955 (CanLII), 33 CPC (6th) 317, per Myers J - suggests definition includes metadata

R v Ball, 2019 BCCA 32 (CanLII), 371 CCC (3d) 381, per Dickson JA, at para 67 ("Facebook posts and messages, emails and other forms of electronic communication fall within the definition of an “electronic document”.") - ↑ R v AS, 2020 ONCA 229 (CanLII), per Paciocco JA, at para 28

- ↑ R v JV, 2015 ONCJ 837 (CanLII), per Paciocco J

- ↑

R v Duroche, 2019 SKCA 97 (CanLII), per Schwann JA, at para 77

R v Hirsch, 2017 SKCA 14 (CanLII) (working hyperlinks pending), per Caldwell JA, at para 24

R v Richardson, 2020 NBCA 35 (CanLII), per Lavigne JA, at para 22

R v Ball, 2019 BCCA 32 (CanLII), 371 CCC (3d) 381, per Dickson JA, at para 67

R v Martin, 2021 NLCA 1 (CanLII), per Hoegg JA, at para 25 - ↑ R v Sohail, 2018 ONCJ 566 (CanLII), per Felix J, at paras 51 to 55

- ↑ R v Rowe, 2012 ONSC 2600 (CanLII), per Howden J, at para 24

- ↑ R v R v Nichols, 2004 OJ 6186(*no CanLII links)

- ↑ R v Stewart, 2006 OJ(complete citation pending)

- ↑ JV, supra

- ↑ R v Piercey, 2012 ONCJ 500 (CanLII), per Pugsley J

Elements of Admission

The requirements for admission of an electronic document are:

- Authenticity

- Integrity / Reliability

- Not Hearsay

- Relevant and Material

The first two steps of authenticity and integrity/reliability are governed exclusively by s. 31.1 to 31.3 of the Canada Evidence Act. Establishing the second step includes the requirement that the form of the evidence satisfies the "best evidence rule" in addition to requiring that the evidence itself is sufficiently reliable. Section 31.3 provides a statutory shortcut to proof of integrity through the proof of integrity of the document system. However, even where the shortcut fails, the evidence can still be admitted through common law proof of reliability.[1]

- ↑

R v Hamdan, 2017 BCSC 676 (CanLII), 349 CCC (3d) 338, per Butler J

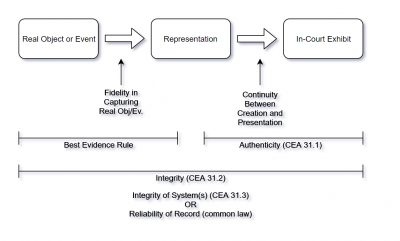

Authentication

"Authentication” refers to whether the record “is what it purports to be“.[1] It does not mean that the document is "genuine", only that there is some evidence supporting what it appears to be.[2] There is no requirement that the document be proven to be "actually true or reliable."[3]

The burden is upon the party tendering the electronic document to prove its authenticity:

- Authentication of electronic documents

31.1 Any person seeking to admit an electronic document as evidence has the burden of proving its authenticity by evidence capable of supporting a finding that the electronic document is that which it is purported to be.

2000, c. 5, s. 56.

The proof of authentication is as condition precedent to admission of records.[4]

There is "no objective standard to measure sufficiency"[5]

The standard under s. 31.1 has been described as simply requiring evidence "capable of supporting a finding that the electronic document is as it claims [or purports] to be". There must be "some evidence of authenticity."[6] This standard is merely a threshold test that permits the evidence to be considered for "ultimate evaluation" and nothing more.[7] The threshold for authenticity should be "low" or "modest."[8]

The intention of the low standard is because ultimate authenticity is best resolved using the contexts of all the evidence. The initial threshold question is simply to assess whether there is any merit to assess the evidence at the end of trial.[9]

Authentication is not the same as proving authorship, which is part of the ultimate determination.[10]

This evidence can be direct or circumstantial.[11]

- No Proof of Integrity

At the authentication stage, the judge is not to consider the "integrity" of the evidence, which is the focus of analysis on s. 31.2 relating to the "best evidence rule."[12]

There is some suggestion that the party seeking admission of the record has the burden to establish the absence of any tampering.[13] However, it should not be taken too far when it comes to electronic records, including internet sourced records, since all electronic documents have the potential to be manipulated in some way.[14]

- ↑ David Paciocco, "Proof and Progress", at p. 197 (“Evidence can be “authenticated” even where there is a contest over whether it is what it purports to be. This is so even though there have been situations where individuals have created false Facebook pages in the name of others, or where information has been added by others to someone’s website or social medium home page... and there have been cases where email messages have been forged”)

- ↑ R v Martin, 2021 NLCA 1 (CanLII), per Hoegg JA (2:1), at para 49

- ↑ Martin, ibid., at para 49

- ↑

R v Avanes, 2015 ONCJ 606 (CanLII), 25 CR (7th) 26, per Band J

- ↑

FH v McDougall, 2008 SCC 53 (CanLII), [2008] 3 SCR 41, per Rothstein J

- ↑

R v Hirsch, 2017 SKCA 14 (CanLII), 353 CCC (3d) 230, per Caldwell JA, at para 18 (" The provision merely requires the party seeking to adduce an electronic document into evidence to prove that the electronic document is what it purports to be. This may be done through direct or circumstantial evidence: ... Quite simply, to authenticate an electronic document, counsel could present it to a witness for identification and, presumably, the witness would articulate some basis for authenticating it as what it purported to be ... That is, while authentication is required, it is not an onerous requirement ... The burden of proving authenticity of an electronic document is on the person who seeks its admission. The standard of proof required is the introduction of evidence capable of supporting a finding that the electronic document is as it claims to be. In essence, the threshold is met and admissibility achieved by the introduction of some evidence of authenticity.")

R v CL, 2017 ONSC 3583 (CanLII), per Baltman J, at para 21 ("The common law imposes a relatively low standard for authentication; all that is needed is “some evidence” to support the conclusion that the thing is what the party presenting it claims it to be.")

R v Farouk, 2019 ONCA 662 (CanLII), per Harvison Young JA, at para 60

R v CB, 2019 ONCA 380 (CanLII), 146 OR (3d) 1, per Watt JA, at para 68 - ↑

CL, ibid., at para 21 citing Pacioccco - ("As Paciocco states, for the purposes of admissibility authentication is “nothing more than a threshold test requiring that there be some basis for leaving the evidence to the fact-finder for ultimate evaluation”:")

- ↑ Martin, supra, at para 43

- ↑

Hirsch, supra at para 84

Martin, supra, at para 41 - ↑ Martin, ibid., at para 53

- ↑ Farouk, supra, at para 60 CB, supra, at para 68

- ↑

Hirsch, ibid., at para 18 ("...the integrity (or reliability) of the electronic document is not open to attack at the authentication stage of the inquiry. Those questions are to be resolved under s. 31.2 of the Canada Evidence Act—i.e., the best evidence rule, as it relates to electronic documents.")

- ↑ R v Andalib-Goortani, 2014 ONSC 4690 (CanLII), 13 CR (7th) 128, per Trotter J, at paras 28 to 29 (photograph inadmissible due to inability to authenticate it where metadata stripped from the file)

- ↑

R v Clarke, 2016 ONSC 575 (CanLII), per Allen J, at para 119

Specific Circumstances

- Authentication of Identity Evidence

Where the identity of the accused whose communication is found an electronic document is in dispute, the proof of authenticity requires that the Crown adducing the evidence show:[1]

- "a preliminary determination must be made as to whether, on the basis of evidence admissible against the accused, the Crown has established on a balance of probabilities that the statement is that of the accused" and

- "If this threshold is met, the trier of fact should then consider the contents of the statement along with other evidence to determine the issue of innocence or guilt."

When proffering social media account evidence to establish identity, it is significant there be some evidence indicating where the user logged in from, particularly where the accused would claim the postings were faked or from someone else using his account.[2]

- Authentication of cell phone evidence

In relation to the admission of text messages found on a cell phone, the question of who sent the text messages is an issue of authentication and relevance not hearsay.[3] Where the party adducing the evidence cannot prove who sent the message then they are not reliable."[4]

Proof of identity of the sender which is relevant to authentication and reliability should include elements such as:[5]

- recorded purchaser and subscriber;

- usage being consistent with the activities of the alleged user;

- location where the phone was used

- observational evidence of "exclusive or non-exclusive use" of the cell phone;

- contents of the cell phone text messages and telephone calls;

- patterns in cellphone and text message communications including the messages themselves; and

- evidence from witnesses who received communications from a cell phone and who can identify the source of those communications.

Linking a facebook account to an email address known to be used by the accused can be sufficient to authenticate facebook chat log.[6]

- Authentication of Social Media and Web Evidence

Screenshots of a website are not admissible simply as being forms of photograph and must comply with the s. 31.1 to 31.8 of the Evidence Act.[7] However, it will usually be sufficient to have the account owner, or a party to a chat log, authenticate the records as accurate.[8] This is not always necessary, and it can be authenticated by someone other than the person taking the screenshot as long as they have some first-hand familiarity with the contents of the website.[9]

Even a person with limited technological experience and knowledge can authenticate social media.[10]

A website record that shows a phone number matching the phone number of the accused can be enough to satisfy authenticity.[11]

Absent testimony explaining the social media exhibit, including what it depicts and what it means, may render the exhibit inadmissible.[12]

- Time Stamps on Communications

To authenticate the "time stamps" for a message, there should be at least some evidence "direct or circumstantial", regarding the "accuracy or reliability of the computer-generated time stamp."[13]

- ↑

R v Evans, 1993 CanLII 86 (SCC), [1993] 3 SCR 653, per Sopinka J, at para 32

R v Moazami, 2013 BCSC 2398 (CanLII), per Butler J, at para 12 (re admission of facebook messages)

- ↑ R v Ball, 2019 BCCA 32 (CanLII), 371 CCC (3d) 381, per Dickson JA, at para 86

- ↑

R v Vader, 2016 ABQB 287 (CanLII), per Thomas J, at para 14

R v Serhungo, 2015 ABCA 189 (CanLII), 324 CCC (3d) 491, per O'Ferrall JA, at para 77 appealed on other issue at 2016 SCC 2 (CanLII), per Moldaver J

- ↑

Vader, supra, at para 15

Serhungo, supra, at para 86

- ↑

Vader, supra, at para 17

- ↑

R v Harris, 2010 PESC 32 (CanLII), per Mitchell J

- ↑

R v Bernard, 2016 NSSC 358 (CanLII), per Gogan J, at para 44

R v Soh, 2014 NBQB 20 (CanLII), 1079 APR 328, per Lavigne J

R v Moazami, 2013 BCSC 2398 (CanLII), per Butler J

- ↑

Bernard, supra, at para 49

Hirsch, supra, at para 18 ("Quite simply, to authenticate an electronic document, counsel could present it to a witness for identification and, presumably, the witness would articulate some basis for authenticating it as what it purported to be ... That is, while authentication is required, it is not an onerous requirement.")

- ↑ e.g. Hirsch, supra - complainant authenticated facebook post despite having seen it only through a friend

- ↑

R v Lowrey, 2016 ABPC 131 (CanLII), 357 CRR (2d) 76, per Rosborough J- mother prints out facebook page of child

- ↑ Farouk, supra

- ↑ Ball, supra

- ↑ Ball, ibid., at para 85

Best Evidence Rule and Reliability

The best evidence rule assesses the reliability of the contents of a record. This is separate from the question of authentication, which concerns the veracity (or genuineness) of the record's character.

- Purpose

The rule "seek[s] to ensure that an electronic document offered in court accurately reflects the original information that was inputted into a document". It is not concerned with whether the data, at the time it is inputted, was accurate whatsoever. It is only concerned with "what might happen after the information has been inputted."[1]

- Legal Requirements

The "best evidence rule" for electronic records can be satisfied by establishing either:[2]

- "the integrity of the electronic documents system" that generated the document (s. 31.2(1)(a)) which is presumed (s. 31.3, see "presumption of integrity" below).

- in the case of printouts, that the "printout has been manifestly or consistently acted on, relied on or used as a record of the information recorded or stored in the printout" (s. 31.2(2))

- the presumption relating to electronic signatures (see s. 31.4)

- Application of best evidence rule — electronic documents

31.2 (1) The best evidence rule in respect of an electronic document is satisfied

- (a) on proof of the integrity of the electronic documents system by or in which the electronic document was recorded or stored; or

- (b) if an evidentiary presumption established under section 31.4 [proof of electronic signatures] applies.

- Printouts

(2) Despite subsection (1) [application of best evidence rule – electronic documents], in the absence of evidence to the contrary, an electronic document in the form of a printout satisfies the best evidence rule if the printout has been manifestly or consistently acted on, relied on or used as a record of the information recorded or stored in the printout.

2000, c. 5, s. 56.

It is suggested that the best evidence rule only applies to records being admitted for the truth of its contents and not real evidence.[3]

- Sources of Evidence

The methods of proving "best evidence" is for "someone familiar with the information originally input" can testify to its accuracy.[4] Alternatively, someone who receives the Document electronically, such as the Recipient of an email or text, who can testify to its accuracy will satisfy the requirement unless The opposing party can show that system was not functioning properly.[5]

The coherence of the document coupled with a properly functioning system will usually be sufficient.[6]

Mechanically generated evidence has various indicta of reliability. It is designed to produce accurate results. It is tested to ensure accuracy. It is mass-produced according to a design and tested. It is usually maintained and calibrated.[7]

The information does not need to be perfect, infaliable, or accurate to certainty. Flawed evidence is routinely admitted and the weight is assessed by the trier-of-fact.[8]

- Social Media Evidence

Given the impermanence of online evidence it can be that screenshots will be found to be the "best evidence" available.[9]

Investigators taking screenshots of social media accounts the integrity can be supported by recording time and date of the capture of the image as well as recording metadata, including URL data and underlying sourcecode for the webpage.[10]

- ↑ David Paciocco, "Proof and Progress" Canadian Journal of Law and Technology at p. 193 ("The best evidence rules applicable to electronic documents from computer and similar devices are not concerned with requiring original documents to be proved, but instead seek to ensure that an electronic document offered in court accurately reflects the original information that was input into a document. To be clear, these best evidence rules are not concerned with whether the original information that was input was accurate information. Documents containing inaccurate information, even a completely forged document offered as a genuine document, can satisfy the best evidence rules. The electronic best evidence rules are concerned with what might happen after the information has been input.")

- ↑ See R v Nde Soh, 2014 NBQB 20 (CanLII), 1079 APR 328, per Lavigne J - admitting facebook chats from testimony of one of the parties to the chat

- ↑

Saturley v CIBC World Markets, 2012 NSSC 226 (CanLII), 1003 APR 388, per Wood J, at para 13 ("If electronic information is determined to be real evidence, the evidentiary rules relating to documents, such as the best evidence and hearsay rules, will not be applicable.")

- ↑ Paciocco, supra at p. 193

- ↑ Paciocco, supra at p. 193 ("Alternatively, if a document appears on its face to be what it is claimed — for example, an email or a text — testimony that it is the document that was received or sent by email or text will be presumed to satisfy the authenticity and “best evidence” requirements, unless the opposing party raises a doubt about whether the computer system was operating properly. ")

- ↑ Paciocco, supra at p. 193 ("Again, the apparent coherence of the document coupled with the fact that it was produced or retrieved in the fashion that a functioning computer would produce or retrieve documents is evidence that the electronic document system was functioning as it should.")

- ↑ Kon Construction Ltd. v. Terranova Developments Ltd. 2015 ABCA 249 (complete citation pending)

- ↑ Kon, ibid.

- ↑

R v Hirsch, 2017 SKCA 14 (CanLII), 353 CCC (3d) 230, per Caldwell JA, at para 24

- ↑ e.g. R v Wolfe, 2022 SKQB 86 (CanLII), per Gerecke J, at para 14

Integrity of Electronic Document System

The authenticity and reliability of electronic documents can be established by "proof of the integrity of the electronic documents system rather than that of the specific electronic document."[1]

Proof of integrity is established by factors including the manner of record, compliance with industry standards, business reliance, and security.[2]

The evidence to show integrity of a records keeping system needs only show that the system was secure and that there was no observable evidence of tampering. There is no need to prove that there was reasonable no way by which records can be tampered with.[3]

Problems with the accuracy and integrity of the system will most typically go to weight rather than the admission of electronic evidence.[4]

Evidence of integrity can be from any source including a third party to the creation of the record.[5]

- Integrity of the Place the Evidence was Recorded or Stored

To rely on the presumption of integrity, the party adducing the electronic evidence must prove not only that the system that created the record, but also the system that stored the evidence, which may be a separate device entirely.[6]

- Integrity of text messages

Evidence of integrity can include evidence of coherent logs that one expects to see on the device and the fact that the device turns on properly.[7]

However, evidence that data was successfully extracted from a phone is not evidence that the device was functioning properly.[8]

- ↑

R v Nde Soh, 2014 NBQB 20 (CanLII), 1079 APR 328, per Lavigne J, at para 25

- ↑ R v Oler, 2014 ABPC 130 (CanLII), 590 AR 272, per Lamoureux J , at para 7

- ↑

R v Clarke, 2016 ONSC 575 (CanLII), per Allen J

- ↑ Saturley v CIBC World Markets, 2012 NSSC 226 (CanLII), 1003 APR 388, per Wood J, at paras 22 to 26

- ↑

R v Hirsch, 2017 SKCA 14 (CanLII), 353 CCC (3d) 230, per Caldwell JA

R v Lowrey, 2016 ABPC 131 (CanLII), 357 CRR (2d) 76, per Rosborough J (mother printed screenshots of child's social media account) - ↑

e.g. R v Bernard, 2016 NSSC 358 (CanLII), per Gogan J, at para 52 ("the Crown made no attempt to prove the integrity of the electronic documents system in which the evidence was recorded or stored." [emphasis added])

- ↑

R v Schirmer, 2020 BCSC 2260 (CanLII), per Crabtree J, at paras 31 and 36 to 37

- ↑ Schirmer, ibid., at para 34

Presumption of Integrity

Under s. 31.3, in "absence of evidence to the contrary", the integrity of electronic documents are presumed where the is evidence of at least one of the following:

- "that at all material times the computer system or other similar device used by the electronic documents system was operating properly" (s. 31.3(a));

- if the device was not operating properly at all material times, that the malfunction "did not affect the integrity of the electronic document and there are no other reasonable grounds to doubt the integrity of the electronic documents system" (s. 31.3(a));

- that "the electronic document was recorded or stored by a party who is adverse in interest to the party seeking to introduce it";(s. 31.3(b)) or

- the document "was recorded or stored in the usual and ordinary course of business by a person who is not a party and who did not record or store it under the control of the party seeking to introduce it." (s. 31.3(c))

- Presumption of integrity

31.3 For the purposes of subsection 31.2(1) [application of best evidence rule – electronic documents], in the absence of evidence to the contrary, the integrity of an electronic documents system by or in which an electronic document is recorded or stored is proven

- (a) by evidence capable of supporting a finding that at all material times the computer system or other similar device used by the electronic documents system was operating properly or, if it was not, the fact of its not operating properly did not affect the integrity of the electronic document and there are no other reasonable grounds to doubt the integrity of the electronic documents system;

- (b) if it is established that the electronic document was recorded or stored by a party who is adverse in interest to the party seeking to introduce it; or

- (c) if it is established that the electronic document was recorded or stored in the usual and ordinary course of business by a person who is not a party and who did not record or store it under the control of the party seeking to introduce it.

2000, c. 5, s. 56.

[annotation(s) added]

- Standard of Proof

The presumption can be invoked where the party adducing the electronic evidence can prove on a standard of balance of probabilities that one of the categories in s. 31.3 applies.[1]

The standard of "evidence capable of supporting" the relevant findings is a "low threshold."[2]

It is not necessary that the Crown prove that the device at issue was in fact functioning properly at all material times.[3]

- Stored or Recorded by Adverse Party

There should be some evidence as to the "origin" of any "screen shots" and "attempt to access" the social media account.[4]

- Lay Evidence

If an operator of a computer device can testify that the device was "working properly at the relevant time", and where no contradictory evidence is found, the Crown can rely on the presumption of integrity.[5]

- ↑

See R v Avanes, 2015 ONCJ 606 (CanLII), 25 CR (7th) 26, per Band J, at para 63

R v CL, 2017 ONSC 3583 (CanLII), per Baltman J, at para 24 (Integrity of the storage system can be established "...under s. 31.2(1)(a), by proving the “integrity of the electronic document system” in which the document was stored. Direct or circumstantial evidence that demonstrates, on the balance of probabilities, that the electronic record in question is an accurate reproduction of the document stored on the computer is sufficient.")

- ↑ R v SH, 2019 ONCA 669 (CanLII), 377 CCC (3d) 335, per Simmons JA, at para 25 ("In my view, the requirement in s. 31.3(a) of the Canada Evidence Act for “evidence capable of supporting” the relevant findings represents a low threshold. This is apparent when s. 31.3(a) is read in context with, for example s. 31.3(b), which requires that it be “established” that an electronic document was recorded or stored by a party adverse in interest.")

- ↑ SH, ibid., at para 28 ("In my view, the appellant’s arguments that it was necessary that the Crown call C.H. to verify the content of the text messages or provide evidence of testing the Samsung cell phone text messaging system is misconceived. In the context of the evidence adduced in this case, that would amount to requiring that it be established that, at all material times, the Samsung cell phone was operating properly. That is not the threshold under s. 31.3(a).")

- ↑

R v Bernard, 2016 NSSC 358 (CanLII), per Gogan J, at para 58

- ↑

R v KM, 2016 NWTSC 36 (CanLII), per Charbonneau J, at paras 36 to 60

R v Burton, 2017 NSSC 3 (CanLII), per Arnold J, at paras 30 to 32

R v MJAH, 2016 ONSC 249 (CanLII), per Fregeau J, at paras 45 to 48

R v Colosie2015 ONSC 1708(*no CanLII links) , at paras 12-27

R v Ghotra, [2015] OJ No 7253{{{2}}}(*no CanLII links) , at paras 148-9

R v CL, 2017 ONSC 3583 (CanLII), per Baltman J, at paras 26 to 27

Rebutting the Presumption

The mere vouching for the contents of a social media website, even if they were not present for the creation of the content, will often be enough to authenticate the evidence, absent rebuttal evidence.[1]

However, evidence suggestive of tampering, including testimony of others with access to the social media account, may be sufficient to undermine the presumption.[2]

- ↑

e.g. R v Nde Soh, 2014 NBQB 20 (CanLII), 1079 APR 328, per Lavigne J

R v KM, 2016 NWTSC 36 (CanLII), per Charbonneau J

R v Hirsch, 2017 SKCA 14 (CanLII), 353 CCC (3d) 230, per Caldwell JA

R v Ball, 2019 BCCA 32 (CanLII), 371 CCC (3d) 381, per Dickson JA, at para 85

- ↑

Ball, supra, at para 85

Admissibility of Contents of Records

Under section 31.7 the party adducing the records must satisfy the general rules of admission:

- Application

31.7 Sections 31.1 to 31.4 [X] do not affect any rule of law relating to the admissibility of evidence, except the rules relating to authentication and best evidence.

2000, c. 5, s. 56.

Once a computer record is authenticated, the records will usually be admissible under one of the following methods of admissibility for the truth of their contents:[1]

- CEA business records (s. 30),

- CEA financial records (s. 29),

- common law business documents,

- principled exception to hearsay, or

- real evidence[2]

- Automated Records

Where compilation was carried out by automated means, it may be possible to admit them through the common law business record method.[3]

Evidence that is "automatically recorded by any means, other than by human labour, and the evidence so recorded can be reproduced in any form, intelligible to the human mind, the reproduction is admissible as real evidence." However, "The weight to be attached to such evidence will depend on the accuracy and integrity of the process employed."[4]

- Profile Information

In certain circumstances, information found on a profile can be inadmissible as hearsay without proof of it being a business record.[5]

- Admission of Electronic Records under the Principled Approach

The analysis of reliability should "be assessed by focusing on the circumstances in which information was generated, recorded, stored, and reproduced.."[6]

- Assessing Probative Value of Text Messages

Where a series of messages are being tendered but have been selected from a larger body of communications, the probative value of the record will be reduced where the exchanges appear to be truncated, taken out of context, and their overall true character or meaning is hard to assess.[7]

- ↑ R v CM, 2012 ABPC 139 (CanLII), 540 AR 73, per Franklin J - review methods of admitting electronic documents, re phone records

- ↑

see R v McCulloch, [1992] BCJ No 2282 (BCPC)(*no CanLII links)

, at para 18 regarding real evidence

see also Saturley v CIBC World Markets Inc, 2012 NSSC 226 (CanLII), 1003 APR 388, per Wood J - makes distinction between automated generated record which is real evidence, and human-made records which are documentary evidence

Animal Welfare International Inc and W3 International Media Ltd., 2013 BCSC 2125 (CanLII), per Ross J - agrees with Saturley - ↑

Eg. R v Sunila, 1986 CanLII 4619 (NS SC), 26 CCC (3d) 331, per MacIntosh J

R v Rideout, [1996] NJ No 341(*no CanLII links)

R v Moisan, 1999 ABQB 875 (CanLII), 141 CCC (3d) 213, per Lee J

R v Monkhouse, 1987 ABCA 227 (CanLII), 61 CR (3d) 343, per Laycraft CJ

- ↑ McCulloch, supra, at para 18

- ↑ R v Rahi, 2023 ONSC 190 (CanLII), per Nakatsuru J

- ↑

R v Nardi, 2012 BCPC 318 (CanLII), per Challenger J, at para 17

- ↑ R v TStewart, 2021 ABQB 256 (CanLII), per Germain J, at para 38

Admission of Non-Document Records

The admission of any form of electronic record must comply with the Canada Evidence Act.

The necessary degree of "authentication" evidence required “depends upon the claim(s) which the tendering party is making about the evidence."[1]

The rules concerning the admission of audio, video, or photographs are substantially the same.[2] It is an open question whether the standard of proof is on the balance of probabilities or the "authentication standard."[3]

- "fair and accurate"

Before accepting any audio or video recording, the judge must inquire whether the video is a "fair and accurate representation of what happened". Failure to do so is a legal error.[4]

- completeness of recording

It is not necessary that the recording be proven as not having been "altered or changed". It is only necessary that it be "substantially fair and accurate."[5]

Merely treating gaps in continuity as a matter only going to weight in an error of law.[6] When contested, there must be an enquiry into whether the recording is "substantially fair and accurate."[7]

- ↑

R v Bulldog, 2015 ABCA 251 (CanLII), 326 CCC (3d) 385, per curiam, at para 32

R v AS, 2020 ONCA 229 (CanLII), per Paciocco JA, at para 27 (“ The outcome of that interpretation matters, for as the Alberta Court of Appeal pointed out in R v Bulldog, ..., what “authentication” requires for the purposes of admissibility “depends upon the claim(s) which the tendering party is making about the evidence”: at para. 32. In this context, the correctness of the trial judge’s admission of the recording turns upon his basis for admitting it.”) - ↑

AS, ibid., at para 28 at footnote 2: ("Bulldog dealt with a video recording, but the principles expressed apply to all reproductions – audio recordings, video recordings and, in my view, photographs: Bulldog, at para. 32. ... ")

Bulldog, supra, at para 32 (“There is an important distinction between recordings (video or audio) and other forms of real evidence (such as a pistol or an article of clothing found at a crime scene) which supports a test of “substantial” accuracy over the appellants’ preferred test of “not altered”. It will be recalled that “authentication” simply requires that the party tendering evidence establish (to the requisite standard of proof, which we discuss below) the claim(s) made about it. What authentication requires in any given instance therefore depends upon the claim(s) which the tendering party is making about the evidence. In the case of most real evidence, the claim is that the evidence is something – the pistol is a murder weapon, or the article of clothing is the victim’s shirt. Chain of custody, and absence of alteration will be important to establish in such cases. In the case of recordings, however, the claim will typically be not that it is something, but that it accurately represents something (a particular event). What matters with a recording, then, is not whether it was altered, but rather the degree of accuracy of its representation. So long as there is other evidence which satisfies the trier of fact of the requisite degree of accuracy, no evidence regarding the presence or absence of any change or alteration is necessary to sustain a finding of authentication.”) - ↑ AS, supra, at para 28 footnote 2: ("...Bulldog did not settle the question of whether the accuracy and fairness of the representation had to be established on the balance of probabilities, or on the lesser authentication standard, requiring only evidence upon which a reasonable trier of fact could conclude that the item is that which it is purported to be. ... The audiotape in this case was an “electronic document” within the meaning of the Canada Evidence Act, R.S., c. E-10, s. 31.8, and therefore arguably subject to the lesser authentication standard, as expressed in s. 31.1. ")

- ↑ AS, ibid., at para 41 ("... If I had found that he admitted the recording as original evidence of the event, I would have found him to have erred by admitting the recording without inquiring into whether it was a fair and accurate representation of what happened.")

- ↑

Bulldog, supra, per curiam, at para 33

AS, supra

compare to: R v Nikolovski, 1996 CanLII 158 (SCC), [1996] 3 SCR 1197, per Cory J (7:2) - ↑ AS, supra, at para 28

- ↑ AS, supra, at paras 28 to 29

Utility of Electronic Evidence

- Inferences of Authorship and Account Ownership

The identity of the author of a communication can be inferred from consideration of a number of indicators:[1]

Evidence visible on the social media account can infer account ownership. This can include:[2]

- profile and other photographs on the account and its resemblance to the accused

- First and last names associated with the account and

- location of residence

- Illustrative of the witness's version of events

A secret recording taken shortly after the offence, can be admitted, without proof of it being "substantially fair and accurate", as "illustrative of the complainant’s version of events."[3]

- Inferences of State of Mind

The presence of social media posts suggesting the accused's attitudes that are relevant to the charges will permit the interference of the accused state of mind at the relevant times. [4]

This will be subject to the requisite balancing of probative value against prejudicial effect.[5]

- ↑

R v JV, 2015 ONCJ 837 (CanLII), per Paciocco J, at para 3

- source of the information

- access to the relevant email or social media account

- disclosure of details known to the proported author

- nature of the exchanges, including whether they relate to matters known to the purported parties

- ↑ R v Christhurajah, 2017 BCSC 1355 (CanLII), per Ehrcke J

- ↑ R v AS, 2020 ONCA 229 (CanLII), per Paciocco JA, at para 29 ("But if the trial judge admitted the recording solely for the more restricted purpose expressed, namely, as a “recording according to [the complainant’s] testimony”, or as “at least in part the assault that she’s described”, then the trial judge did not err in admitting the recording. If the trial judge was not going to rely upon the recording as proof of all that happened while the event was being recorded, there would be need for him to require authentication of the recording as a “substantially accurate and fair recording” of actual events.")

- ↑ e.g. R v Bright, 2017 ONSC 377 (CanLII), per Kurke J, at paras 7 and 16

- ↑

Bright, ibid., at paras 26 to 27

Procedure

Where certain evidence to be adduced in a hearing is considered "electronic documents", there must be a voir dire to determine its admissibility.[1] In a jury trial, the challenge to the authenticity of a social media post from the accused must be determined in absence of the jury.[2]

- Dealing with data in court

842 Despite anything in this Act, a court may create, collect, receive, store, transfer, distribute, publish or otherwise deal with electronic documents if it does so in accordance with an Act or with the rules of court.

2002, c. 13, s. 84.

Proof by Standard, Procedure, Usage or Practice

- Standards may be considered

31.5 For the purpose of determining under any rule of law whether an electronic document is admissible, evidence may be presented in respect of any standard, procedure, usage or practice concerning the manner in which electronic documents are to be recorded or stored, having regard to the type of business, enterprise or endeavour that used, recorded or stored the electronic document and the nature and purpose of the electronic document.

2000, c. 5, s. 56.

- ↑ R v Ball, 2019 BCCA 32 (CanLII), 371 CCC (3d) 381, per Dickson JA, at para 67 ("As with other admissibility issues, where there is reason to question whether an electronic document meets the statutory requirements, a voir dire should be held and a reasoned determination made as to its admissibility. This step is particularly important in the context of a jury trial: ")

- ↑ Ball, ibid., at para 87 (" It is sufficient to say there is a realistic possibility that, properly scrutinized, the judge may have justifiably excluded or limited the evidentiary use of the photographs. In these circumstances, in the absence of a clear concession from counsel, the judge should have made these determinations in the first instance, on a voir dire, in the absence of the jury.")

Proof by Affidavit

- Proof by affidavit

31.6 (1) The matters referred to in subsection 31.2(2) [electronic records – print-outs] and sections 31.3 [electronic records – presumption of integrity] and 31.5 [electronic records – proof by standard, procedure, usage or practice] and in regulations made under section 31.4 [proof of electronic signatures] may be established by affidavit.

- Cross-examination

(2) A party may cross-examine a deponent of an affidavit referred to in subsection (1) [electronic records – proof by affidavit] that has been introduced in evidence

- (a) as of right, if the deponent is an adverse party or is under the control of an adverse party; and

- (b) with leave of the court, in the case of any other deponent.

2000, c. 5, s. 56.

[annotation(s) added]

Expert Evidence for Admissibility

Courts have taken a "functional approach" to the proof that a device was "operating properly" under s. 31.3(a)[1]

Proper operation of a device can be established with lay evidence that is either direct or circumstantial.[2]

Expert evidence may be required to "explain the meaning of the computer-generated information or the accuracy or reliability of the generating technology". Nevertheless, circumstantial evidence and lay witness testimony "is often sufficient."[3]

The admission of certain electronic evidence from "mundane" or "commonplace" technology (such as social media websites or cell phone text messages) can be authenticated without expert evidence when testified to by a user well versed in the functionality of the device and meaning of the contents.[4]

Proof of authenticity of the record and integrity of the system can be proven either by expert evidence or by circumstantial evidence. [5] Expert evidence is preferred when authenticating the results from an extraction of an electronic device.[6]

- Authenticating Electronic Records Without Opinion Evidence

Where the authenticity and admissibility is not being disputed there it should not be necessary to call any expert evidence in order to admit any digital evidence such as facebook, email or text messages.[7] The trier of fact can assess the weight of the evidence without expert evidence, and account for the possibility of fabrication, editing or deletion, based on the testimony of the parties involved in the communication.[8]

A person testifying to specialized knowledge will not necessarily be required to be qualified as an expert. Where they testify to their "factual knowledge" based on their "knowledge, observations and experience."[9]

It has been accepted that technical evidence describing the "general rule and its exceptions" of the functioning of complex systems is not opinion evidence where the "understand[ing] the scientific and technical underpinnings" are not necessary to give reliable descriptions.[10]

An expert who testifies to direct observation without opinion is not subject to the opinion rule of exclusion. This evidence is admitted in the same way as eye-witness evidence.[11]

- ↑ R v Richardson, 2020 NBCA 35 (CanLII), per Lavigne JA, at para 31

- ↑ Richardson, ibid., at para 31

- ↑

R v Ball, 2019 BCCA 32 (CanLII), 371 CCC (3d) 381, per Dickson JA, at para 69 ("Depending on the circumstances, expert evidence may be required to explain the meaning of the computer-generated information or the accuracy or reliability of the generating technology, although, in the absence of cause for doubt, circumstantial evidence or lay witness testimony is often sufficient. Regardless, expert evidence is not required to explain generally how commonplace technologies such as Facebook, text messaging or email operate if a lay witness familiar with their use can give such testimony")

Richardson, supra, at para 31 ("Expert testimony may be needed if the evidence is proffered for the technological workings of an application that goes beyond what an everyday user would understand.") - ↑

See Paciocco, "Proof and Progress" Canadian Journal of Law and Technology, at pp. 184-186, 188, 198, 211

R v Bulldog, 2015 ABCA 251 (CanLII), 326 CCC (3d) 385, per curiam

See also R v Nde Soh, 2014 NBQB 20 (CanLII), 1079 APR 328, per Lavigne J, at paras 27 to 30

R v KM, 2016 NWTSC 36 (CanLII), per Charbonneau J, at paras 12 to 15, 40 to 44

R v Walsh, 20201 ONCA 43 (CanLII), per Gillese JA, at para 78("The general functioning of iPhones today is not the stuff of experts. iPhone users can explain what applications are and what use they make of them. And the triers of fact do not need the assistance of persons with specialized knowledge in order to form correct judgments on matters relating to video messaging applications such as FaceTime. The fact that FaceTime sends and [page283] receives video images is uncontroversial. So, too, is the capability of the recipient of a FaceTime call to take and print out a screen shot")

Ball, supra, at para 69 ("...expert evidence is not required to explain generally how commonplace technologies such as Facebook, text messaging or email operate if a lay witness familiar with their use can give such testimony") - ↑

R v Avanes, 2015 ONCJ 606 (CanLII), 25 CR (7th) 26, per Band J, at paras 64 to 67

- ↑ Avanes, ibid., at para 65 -- judge suggests expert evidence could be simply admitted through affidavit.

- ↑

Ducharme v Borden, 2014 MBCA 5 (CanLII), 303 Man R (2d) 81, per Mainella JA, at paras 15 to 17 (re civil proceedings where parties to communication testified, applying The Manitoba Evidence Act)

- ↑

Ducharme v Borden, ibid., at para 17 (“ Once the electronic media evidence was agreed to be admissible, it was up to the judge to decide how much weight to give to it in view of testimony he heard that aspects of that evidence may have been edited or fabricated. In our view, a court is quite capable of assessing the weight to give to electronic documents, without the assistance of an expert, when the witnesses to the communications testify and for whom credibility findings can be made on allegations of fabrication, editing or deletion of communications.“)

- ↑

R v Hamilton, 2011 ONCA 399 (CanLII), 271 CCC (3d) 208, per curiam, at paras 273 to 284 - evidence from phone company as to the mechanical workings of cell towers and their relationship to the cell phone

R v Ranger, 2010 ONCA 759 (CanLII), OJ No 4840, per curiam -- cell phone tower evidence

cf. R v Korski, 2009 MBCA 37 (CanLII), 244 CCC (3d) 452, per Steel JA -- required expert to testify on cell tower evidence

- ↑ Hamilton, supra, at to 274 paras 273 to 274{{{3}}}, 277

- ↑

R v KA, 1999 CanLII 3793 (ON CA), 137 CCC (3d) 225, per Charron JA, at para 72

Definitions

- Definitions

31.8 The definitions in this section apply in sections 31.1 to 31.6 [electronic records].

"computer system" means a device that, or a group of interconnected or related devices one or more of which,

- (a) contains computer programs or other data; and

- (b) pursuant to computer programs, performs logic and control, and may perform any other function.

"data" means representations of information or of concepts, in any form.

"electronic document" means data that is recorded or stored on any medium in or by a computer system or other similar device and that can be read or perceived by a person or a computer system or other similar device. It includes a display, printout or other output of that data.

"electronic documents system" includes a computer system or other similar device by or in which data is recorded or stored and any procedures related to the recording or storage of electronic documents.

"secure electronic signature" means a secure electronic signature as defined in subsection 31(1) of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act.

2000, c. 5, s. 56.

[annotation(s) added]

A "computer system" will include home computers, smartphones, and other computing devices.[1]

Section 31(1) of the PIPEDA states:

secure electronic signature means an electronic signature that results from the application of a technology or process prescribed by regulations made under subsection 48(1). (signature électronique sécurisée)

– PIPEDA

- ↑ R v Ball, 2019 BCCA 32 (CanLII), 371 CCC (3d) 381, per Dickson JA, at para 67 (“ Facebook posts and messages, emails and other forms of electronic communication fall within the definition of an “electronic document”. Home computers, smartphones and other computing devices fall within the definition of a “computer system”. Accordingly, the admissibility of Facebook messages and other electronic communications recorded or stored in a computing device is governed by the statutory framework. As with other admissibility issues, where there is reason to question whether an electronic document meets the statutory requirements, a voir dire should be held and a reasoned determination made as to its admissibility. This step is particularly important in the context of a jury trial:“)

Receipt of Sworn Documents

- Oaths

846. If under this Act an information, an affidavit or a solemn declaration or a statement under oath or solemn affirmation is to be made by a person, the court may accept it in the form of an electronic document if

- (a) the person states in the electronic document that all matters contained in the information, affidavit, solemn declaration or statement are true to his or her knowledge and belief;

- (b) the person before whom it is made or sworn is authorized to take or receive informations, affidavits, solemn declarations or statements and he or she states in the electronic document that the information, affidavit, solemn declaration or statement was made under oath, solemn declaration or solemn affirmation, as the case may be; and

- (c) the electronic document was made in accordance with the laws of the place where it was made.

2002, c. 13, s. 84.

- Copies

847. Any person who is entitled to obtain a copy of a document from a court is entitled, in the case of a document in electronic form, to obtain a printed copy of the electronic document from the court on payment of a reasonable fee determined in accordance with a tariff of fees fixed or approved by the Attorney General of the relevant province.

2002, c. 13, s. 84.

Receipt of Electronic Documents

Section 842 permits courts to "create, collect, receive, store, transfer, distribute, publish or otherwise deal with electronic documents" in accordance with the Code or rules of court.

- Transfer of data

843 (1) Despite anything in this Act, a court may accept the transfer of data by electronic means if the transfer is made in accordance with the laws of the place where the transfer originates or the laws of the place where the data is received.

- Time of filing

(2) If a document is required to be filed in a court and the filing is done by transfer of data by electronic means, the filing is complete when the transfer is accepted by the court.

2002, c. 13, s. 84.

- Documents in writing

844. A requirement under this Act that a document be made in writing is satisfied by the making of the document in electronic form in accordance with an Act or the rules of court.

2002, c. 13, s. 84.

Electronic Signatures

- Presumptions regarding secure electronic signatures

31.4 The Governor in Council may make regulations establishing evidentiary presumptions in relation to electronic documents signed with secure electronic signatures, including regulations respecting

- (a) the association of secure electronic signatures with persons; and

- (b) the integrity of information contained in electronic documents signed with secure electronic signatures.

2000, c. 5, s. 56.

Sections 2 to 5 of the Secure Electronic Signature Regulations, SOR/2005-30 states that:

- Technology or Process

2 For the purposes of the definition secure electronic signature in subsection 31(1) of the Act, a secure electronic signature in respect of data contained in an electronic document is a digital signature that results from completion of the following consecutive operations:

- (a) application of the hash function to the data to generate a message digest;

- (b) application of a private key to encrypt the message digest;

- (c) incorporation in, attachment to, or association with the electronic document of the encrypted message digest;

- (d) transmission of the electronic document and encrypted message digest together with either

- (i) a digital signature certificate, or

- (ii) a means of access to a digital signature certificate; and

- (e) after receipt of the electronic document, the encrypted message digest and the digital signature certificate or the means of access to the digital signature certificate,

- (i) application of the public key contained in the digital signature certificate to decrypt the encrypted message digest and produce the message digest referred to in paragraph (a),

- (ii) application of the hash function to the data contained in the electronic document to generate a new message digest,

- (iii) verification that, on comparison, the message digests referred to in paragraph (a) and subparagraph (ii) are identical, and

- (iv) verification that the digital signature certificate is valid in accordance with section 3.

3 (1) A digital signature certificate is valid if, at the time when the data contained in an electronic document is digitally signed in accordance with section 2, the certificate

- (a) is readable or perceivable by any person or entity who is entitled to have access to the digital signature certificate; and

- (b) has not expired or been revoked.

(2) In addition to the requirements for validity set out in subsection (1), when the digital signature certificate is supported by other digital signature certificates, in order for the digital signature certificate to be valid, the supporting certificates must also be valid in accordance with that subsection.

4 (1) Before recognizing a person or entity as a certification authority, the President of the Treasury Board must verify that the person or entity has the capacity to issue digital signature certificates in a secure and reliable manner within the context of these Regulations and paragraphs 48(2)(a) to (d) of the Act.

(2) Every person or entity that is recognized as a certification authority by the President of the Treasury Board shall be listed on the website of the Treasury Board Secretariat.

- Presumption

5 When the technology or process set out in section 2 is used in respect of data contained in an electronic document, that data is presumed, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, to have been signed by the person who is identified in, or can be identified through, the digital signature certificate.

– Regs

Section 845 also states:

- Signatures

845 If this Act requires a document to be signed, the court may accept a signature in an electronic document if the signature is made in accordance with an Act or the rules of court.

2002, c. 13, s. 84.