Beyond a Reasonable Doubt: Difference between revisions

m Text replacement - "(R v [A-Z]+)," to "''$1''," |

m Text replacement - "(R v [A-Z][a-z]+)," to "''$1''," |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

The standard of "reasonable doubt" consists of a doubt based on reason and common sense which must be logically based upon the evidence or lack of evidence. It is not based on "sympathy or prejudice". <ref> | The standard of "reasonable doubt" consists of a doubt based on reason and common sense which must be logically based upon the evidence or lack of evidence. It is not based on "sympathy or prejudice". <ref> | ||

R v Lifchus, [http://canlii.ca/t/1fqzt 1997 CanLII 319] (SCC), [1997] 3 SCR 320{{perSCC|Cory J}} (9:0) at para 36<br> | ''R v Lifchus'', [http://canlii.ca/t/1fqzt 1997 CanLII 319] (SCC), [1997] 3 SCR 320{{perSCC|Cory J}} (9:0) at para 36<br> | ||

See also: In ''R v JMH'', [http://canlii.ca/t/fnbb2 2011 SCC 45] (CanLII){{perSCC|Cromwell J}} (9:0) at para 39 ( “a reasonable doubt does not need to be based on the evidence; it may arise from an absence of evidence or a simple failure of the evidence to persuade the trier of fact to the requisite level of beyond reasonable doubt.”) </ref> | See also: In ''R v JMH'', [http://canlii.ca/t/fnbb2 2011 SCC 45] (CanLII){{perSCC|Cromwell J}} (9:0) at para 39 ( “a reasonable doubt does not need to be based on the evidence; it may arise from an absence of evidence or a simple failure of the evidence to persuade the trier of fact to the requisite level of beyond reasonable doubt.”) </ref> | ||

'''Constitutional Foundation'''<Br> | '''Constitutional Foundation'''<Br> | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

Lifchus{{supra}} at para 36</ref> | Lifchus{{supra}} at para 36</ref> | ||

The burden of proof placed upon the Crown lies “much closer to absolute certainty than to a balance of probabilities.”<ref>R v Starr, [http://canlii.ca/t/525l 2000 SCC 40] (CanLII){{perSCC|Iacobucci J}} (5:4) at para 242</ref> The standard is more "than proof that the accused is probably guilty" in which case the judge must acquit.<ref> | The burden of proof placed upon the Crown lies “much closer to absolute certainty than to a balance of probabilities.”<ref>''R v Starr'', [http://canlii.ca/t/525l 2000 SCC 40] (CanLII){{perSCC|Iacobucci J}} (5:4) at para 242</ref> The standard is more "than proof that the accused is probably guilty" in which case the judge must acquit.<ref> | ||

Lifchus{{supra}} at 36</ref> | Lifchus{{supra}} at 36</ref> | ||

To know something with "absolute certainty" is to "know something beyond the possibility of any doubt whatsoever". <ref> | To know something with "absolute certainty" is to "know something beyond the possibility of any doubt whatsoever". <ref> | ||

R v Layton, [http://canlii.ca/t/217bw 2008 MBCA 118] (CanLII){{perMBCA|Hamilton JA}} (2:1) | ''R v Layton'', [http://canlii.ca/t/217bw 2008 MBCA 118] (CanLII){{perMBCA|Hamilton JA}} (2:1) | ||

</ref> | </ref> | ||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

The standard of BARD only applies to the evaluation of the evidence as a whole and not individual aspects of the evidence.<ref> | The standard of BARD only applies to the evaluation of the evidence as a whole and not individual aspects of the evidence.<ref> | ||

R v Stewart, [http://canlii.ca/t/1z6bm 1976 CanLII 202], [1977] 2 SCR 748{{perSCC|Pigeon J}} (6:3) at 759-61<br> | ''R v Stewart'', [http://canlii.ca/t/1z6bm 1976 CanLII 202], [1977] 2 SCR 748{{perSCC|Pigeon J}} (6:3) at 759-61<br> | ||

R v Morin, [http://canlii.ca/t/1ftc2 1988 CanLII 8], [1988] 2 SCR 345 at 354, 44 CCC (3d) 193{{perSCC|Sopinka J}}<br> | ''R v Morin'', [http://canlii.ca/t/1ftc2 1988 CanLII 8], [1988] 2 SCR 345 at 354, 44 CCC (3d) 193{{perSCC|Sopinka J}}<br> | ||

R v White, [http://canlii.ca/t/1fqqt 1998 CanLII 789], [1998] 2 SCR 72, 125 CCC (3d) 385{{perSCC|Major J}} (7:0) at paras 38-41</ref> | ''R v White'', [http://canlii.ca/t/1fqqt 1998 CanLII 789], [1998] 2 SCR 72, 125 CCC (3d) 385{{perSCC|Major J}} (7:0) at paras 38-41</ref> | ||

The standard should be applied for the purpose of determining whether individual elements are proven beyond a reasonable doubt.<ref> | The standard should be applied for the purpose of determining whether individual elements are proven beyond a reasonable doubt.<ref> | ||

R v McKay, [http://canlii.ca/t/gx2z0 2017 SKCA 4] (CanLII){{perSKCA|Whitmore JA}} (3:0) at para 18 ("The standard of proof, being beyond a reasonable doubt, is not to be applied to individual pieces of evidence. Rather, it is to be applied to the evidence as a whole for the purpose of determining whether each of the necessary elements of an offence has been established.")<br> | R v McKay, [http://canlii.ca/t/gx2z0 2017 SKCA 4] (CanLII){{perSKCA|Whitmore JA}} (3:0) at para 18 ("The standard of proof, being beyond a reasonable doubt, is not to be applied to individual pieces of evidence. Rather, it is to be applied to the evidence as a whole for the purpose of determining whether each of the necessary elements of an offence has been established.")<br> | ||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

'''Inferences and Conjecture'''<Br> | '''Inferences and Conjecture'''<Br> | ||

Reasonable doubt must come as a rational conclusion from the evidence available and not as a basis of conjecture.<Ref> | Reasonable doubt must come as a rational conclusion from the evidence available and not as a basis of conjecture.<Ref> | ||

R v Wild, [http://canlii.ca/t/1xd3d 1970 CanLII 148] (SCC), [1971] SCR 101{{Plurality}} at 113</ref> | ''R v Wild'', [http://canlii.ca/t/1xd3d 1970 CanLII 148] (SCC), [1971] SCR 101{{Plurality}} at 113</ref> | ||

<!-- | <!-- | ||

Where the issue is the reliability or credibility of a witness, the courts must generally consider corroborative evidence.<ref> | Where the issue is the reliability or credibility of a witness, the courts must generally consider corroborative evidence.<ref> | ||

R v Kehler, [http://canlii.ca/t/1ggzb 2004 SCC 11] (CanLII), [2004] 1 SCR 328{{perSCC|Fish J}} (7:0) at paras 12-23</ref> | ''R v Kehler'', [http://canlii.ca/t/1ggzb 2004 SCC 11] (CanLII), [2004] 1 SCR 328{{perSCC|Fish J}} (7:0) at paras 12-23</ref> | ||

--> | --> | ||

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

'''Jury Instructions'''<Br> | '''Jury Instructions'''<Br> | ||

The standard should not be articulated in a way that would likely cause the standard to be applied subjectively.<ref> | The standard should not be articulated in a way that would likely cause the standard to be applied subjectively.<ref> | ||

R v Stubbs, [http://canlii.ca/t/g01lb 2013 ONCA 514] (CanLII){{perONCA|Watt JA}} (3:0) at para 99<br> | ''R v Stubbs'', [http://canlii.ca/t/g01lb 2013 ONCA 514] (CanLII){{perONCA|Watt JA}} (3:0) at para 99<br> | ||

R v Bisson, [http://canlii.ca/t/1fqvv 1998 CanLII 810] (SCC), [1998] 1 SCR 306{{perSCC|Cory J}} (7:0) at p. 311 (SCR) | ''R v Bisson'', [http://canlii.ca/t/1fqvv 1998 CanLII 810] (SCC), [1998] 1 SCR 306{{perSCC|Cory J}} (7:0) at p. 311 (SCR) | ||

</ref> | </ref> | ||

'''Consequence of Reasonable Doubt'''<br> | '''Consequence of Reasonable Doubt'''<br> | ||

The finding of reasonable doubt "is not the same as deciding in any positive way that [the allegations] never happened."<ref> | The finding of reasonable doubt "is not the same as deciding in any positive way that [the allegations] never happened."<ref> | ||

R v Ghomeshi, [http://canlii.ca/t/gnzpj 2016 ONCJ 155] (CanLII){{perONCJ|Horkins J}} at para 140<br> | ''R v Ghomeshi'', [http://canlii.ca/t/gnzpj 2016 ONCJ 155] (CanLII){{perONCJ|Horkins J}} at para 140<br> | ||

</ref> It is simply a finding that the evidence is not of "sufficient clarity" to allow an acceptance of the essential facts to an "acceptable degree of certainty or comfort" sufficient to displace the presumption of innocence.<Ref> | </ref> It is simply a finding that the evidence is not of "sufficient clarity" to allow an acceptance of the essential facts to an "acceptable degree of certainty or comfort" sufficient to displace the presumption of innocence.<Ref> | ||

Ghomeshi{{ibid}} at para 140 and 141<Br> | Ghomeshi{{ibid}} at para 140 and 141<Br> | ||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

==Use of Illustrations in Articulating the Standard== | ==Use of Illustrations in Articulating the Standard== | ||

Examples and illustrations are permissible in describing the standard of BARD as long as it does not takeaway the right to reach their own conclusions.<ref> | Examples and illustrations are permissible in describing the standard of BARD as long as it does not takeaway the right to reach their own conclusions.<ref> | ||

R v Stavroff, [http://canlii.ca/t/1tx8m 1979 CanLII 52] (SCC), [1980] 1 SCR 411{{perSCC|McIntyre J}} (7:0) including p. 416 (SCR) | ''R v Stavroff'', [http://canlii.ca/t/1tx8m 1979 CanLII 52] (SCC), [1980] 1 SCR 411{{perSCC|McIntyre J}} (7:0) including p. 416 (SCR) | ||

</ref> | </ref> | ||

However, the use of illustrations or examples in articulating the standard of BARD is "fraught with difficulty".<ref> | However, the use of illustrations or examples in articulating the standard of BARD is "fraught with difficulty".<ref> | ||

R v Stubbs, [http://canlii.ca/t/g01lb 2013 ONCA 514] (CanLII){{perONCA|Watt JA}} (3:0) at para 98<br> | ''R v Stubbs'', [http://canlii.ca/t/g01lb 2013 ONCA 514] (CanLII){{perONCA|Watt JA}} (3:0) at para 98<br> | ||

R v Bisson, [1998] 1 SCR 306, [http://canlii.ca/t/1fqvv 1998 CanLII 810] (SCC){{perSCC|Cory J}} (7:0) at para 6 ("No matter how carefully they may be crafted, examples of what may constitute proof beyond a reasonable doubt can give rise to difficulties")</ref> The use of examples tends to lower the standard to that of a balance of probabilities and encourage a subjective standard.<ref> | ''R v Bisson'', [1998] 1 SCR 306, [http://canlii.ca/t/1fqvv 1998 CanLII 810] (SCC){{perSCC|Cory J}} (7:0) at para 6 ("No matter how carefully they may be crafted, examples of what may constitute proof beyond a reasonable doubt can give rise to difficulties")</ref> The use of examples tends to lower the standard to that of a balance of probabilities and encourage a subjective standard.<ref> | ||

Stubbs{{supra}} at para 99</ref> | Stubbs{{supra}} at para 99</ref> | ||

| Line 95: | Line 95: | ||

{{seealso|Inferences}} | {{seealso|Inferences}} | ||

A reasonable doubt cannot be based on "speculation or conjecture".<Ref> | A reasonable doubt cannot be based on "speculation or conjecture".<Ref> | ||

R v Henderson, [http://canlii.ca/t/frc2m 2012 NSCA 53] (CanLII){{perNSCA|Saunders JA}} (3:0) at para 40<br> | ''R v Henderson'', [http://canlii.ca/t/frc2m 2012 NSCA 53] (CanLII){{perNSCA|Saunders JA}} (3:0) at para 40<br> | ||

R v White, [http://canlii.ca/t/1mqmc 1994 CanLII 4004] (NS CA){{perNSCA|Chipman JA}} (3:0)<br> | ''R v White'', [http://canlii.ca/t/1mqmc 1994 CanLII 4004] (NS CA){{perNSCA|Chipman JA}} (3:0)<br> | ||

R v Eastgaard, [http://canlii.ca/t/fllm5 2011 ABCA 152] (CanLII){{TheCourtABCA}} (2:1) at para 22, aff’d [http://canlii.ca/t/fqmw7 2012 SCC 11] (CanLII){{perSCC|McLachlin CJ}} (7:0)<br> | ''R v Eastgaard'', [http://canlii.ca/t/fllm5 2011 ABCA 152] (CanLII){{TheCourtABCA}} (2:1) at para 22, aff’d [http://canlii.ca/t/fqmw7 2012 SCC 11] (CanLII){{perSCC|McLachlin CJ}} (7:0)<br> | ||

</ref> | </ref> | ||

The Crown has no burden to "negativing every conjecture to which circumstantial evidence might be consistent with the innocence of the accused."<ref> | The Crown has no burden to "negativing every conjecture to which circumstantial evidence might be consistent with the innocence of the accused."<ref> | ||

R v Tahirsylaj, [http://canlii.ca/t/gfwq9 2015 BCCA 7] (CanLII){{perBCCA|Bennett JA}} (3:0) at para 39<Br> | ''R v Tahirsylaj'', [http://canlii.ca/t/gfwq9 2015 BCCA 7] (CanLII){{perBCCA|Bennett JA}} (3:0) at para 39<Br> | ||

R v Paul (1975), [http://canlii.ca/t/1z6dt 1975 CanLII 185] (SCC), 27 CCC (2d) 1 (S.C.C.), at 6, (1975), [1977] 1 SCR 181, 64 DLR (3d) 491 (S.C.C.){{perSCC|Ritchie J}} (6:3)<Br> | R v Paul (1975), [http://canlii.ca/t/1z6dt 1975 CanLII 185] (SCC), 27 CCC (2d) 1 (S.C.C.), at 6, (1975), [1977] 1 SCR 181, 64 DLR (3d) 491 (S.C.C.){{perSCC|Ritchie J}} (6:3)<Br> | ||

</ref> | </ref> | ||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

The defence is permitted to elicit evidence from witnesses of potential inadequacies in the investigation. Oversights in an investigation "can be particularly important where no defence evidence is called."<Ref> | The defence is permitted to elicit evidence from witnesses of potential inadequacies in the investigation. Oversights in an investigation "can be particularly important where no defence evidence is called."<Ref> | ||

R v Gyimah, [http://canlii.ca/t/2bmkw 2010 ONSC 4055] (CanLII){{perONSC|Healey J}}, at para 20 | ''R v Gyimah'', [http://canlii.ca/t/2bmkw 2010 ONSC 4055] (CanLII){{perONSC|Healey J}}, at para 20 | ||

Bero<Br> | Bero<Br> | ||

</ref> | </ref> | ||

Revision as of 20:53, 12 January 2019

- < Evidence

General Principles

The standard of "beyond a reasonable doubt" (BARD) is a common law standard of proof in criminal matters.[1] This standard is exclusively used in criminal or quasi-criminal proceedings. This includes not only adult criminal trials, but also young offender cases, adult sentencing, and certain provincial penal offences.

The standard of "reasonable doubt" consists of a doubt based on reason and common sense which must be logically based upon the evidence or lack of evidence. It is not based on "sympathy or prejudice". [2]

Constitutional Foundation

The standard as the ultimate burden of proof is "inextricably intertwined with that principle fundamental to all criminal trials, the presumption of innocence".[3] The burden should never shift to the accused.[4]

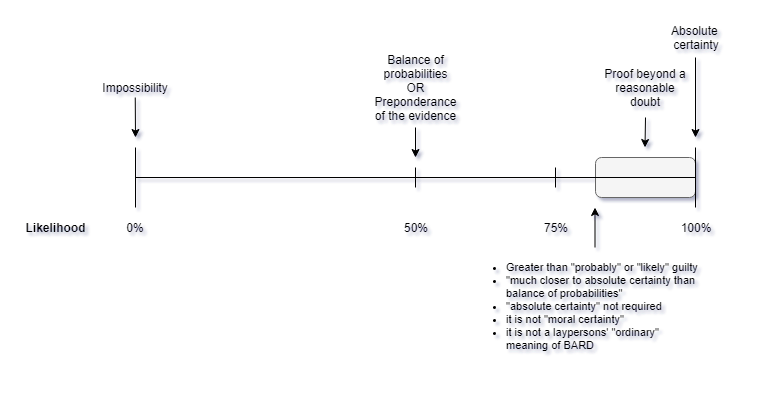

Level of Certainty

Proof beyond a reasonable doubt "it does not involve proof to an absolute certainty; it is not proof beyond any doubt nor is it an imaginary or frivolous doubt."[5]

However, belief that the accused is "probably guilty" is not sufficient and must acquit.[6]

The burden of proof placed upon the Crown lies “much closer to absolute certainty than to a balance of probabilities.”[7] The standard is more "than proof that the accused is probably guilty" in which case the judge must acquit.[8]

To know something with "absolute certainty" is to "know something beyond the possibility of any doubt whatsoever". [9]

Such as standard is "virtually impossible to prove" and "impossibly high" for the Crown to be held to such a standard. [10]

Relationship to Evidence

“[A] reasonable doubt does not need to be based on the evidence; it may arise from an absence of evidence or a simple failure of the evidence to persuade the trier of fact to the requisite level of beyond reasonable doubt.”[11]

The standard of BARD only applies to the evaluation of the evidence as a whole and not individual aspects of the evidence.[12] The standard should be applied for the purpose of determining whether individual elements are proven beyond a reasonable doubt.[13]

Inferences and Conjecture

Reasonable doubt must come as a rational conclusion from the evidence available and not as a basis of conjecture.[14]

Risk of Wrongful Conviction

A verdict of guilt must be considered carefully in order to protect the liberty of the accused and protect against a wrongful conviction.[15]

Jury Instructions

The standard should not be articulated in a way that would likely cause the standard to be applied subjectively.[16]

Consequence of Reasonable Doubt

The finding of reasonable doubt "is not the same as deciding in any positive way that [the allegations] never happened."[17] It is simply a finding that the evidence is not of "sufficient clarity" to allow an acceptance of the essential facts to an "acceptable degree of certainty or comfort" sufficient to displace the presumption of innocence.[18]

- ↑ affirmed under the English common law of England in Woolmington v D.P.P., [1935] A.C. 462 at 481-82 (H.L.)

- ↑

R v Lifchus, 1997 CanLII 319 (SCC), [1997] 3 SCR 320, per Cory J (9:0) at para 36

See also: In R v JMH, 2011 SCC 45 (CanLII), per Cromwell J (9:0) at para 39 ( “a reasonable doubt does not need to be based on the evidence; it may arise from an absence of evidence or a simple failure of the evidence to persuade the trier of fact to the requisite level of beyond reasonable doubt.”) - ↑ Lifchus, supra at para 36

- ↑ Lifchus, supra at para 36

- ↑ Lifchus, supra, at para 31, 36

- ↑ Lifchus, supra at para 36

- ↑ R v Starr, 2000 SCC 40 (CanLII), per Iacobucci J (5:4) at para 242

- ↑ Lifchus, supra at 36

- ↑ R v Layton, 2008 MBCA 118 (CanLII), per Hamilton JA (2:1)

- ↑

Lifchus, supra at para 39

- ↑ R v JMH, supra

- ↑

R v Stewart, 1976 CanLII 202, [1977] 2 SCR 748, per Pigeon J (6:3) at 759-61

R v Morin, 1988 CanLII 8, [1988] 2 SCR 345 at 354, 44 CCC (3d) 193, per Sopinka J

R v White, 1998 CanLII 789, [1998] 2 SCR 72, 125 CCC (3d) 385, per Major J (7:0) at paras 38-41 - ↑

R v McKay, 2017 SKCA 4 (CanLII), per Whitmore JA (3:0) at para 18 ("The standard of proof, being beyond a reasonable doubt, is not to be applied to individual pieces of evidence. Rather, it is to be applied to the evidence as a whole for the purpose of determining whether each of the necessary elements of an offence has been established.")

- ↑ R v Wild, 1970 CanLII 148 (SCC), [1971] SCR 101 at 113

- ↑

R v W(R), 1992 CanLII 56 (SCC), [1992] 2 SCR 122, per McLachlin J (6:0) in context of child witnesses ("Protecting the liberty of the accused and guarding against the injustice of the conviction of an innocent person require a solid foundation for a verdict of guilt")

- ↑

R v Stubbs, 2013 ONCA 514 (CanLII), per Watt JA (3:0) at para 99

R v Bisson, 1998 CanLII 810 (SCC), [1998] 1 SCR 306, per Cory J (7:0) at p. 311 (SCR) - ↑

R v Ghomeshi, 2016 ONCJ 155 (CanLII), per Horkins J at para 140

- ↑

Ghomeshi, ibid. at para 140 and 141

Use of Illustrations in Articulating the Standard

Examples and illustrations are permissible in describing the standard of BARD as long as it does not takeaway the right to reach their own conclusions.[1] However, the use of illustrations or examples in articulating the standard of BARD is "fraught with difficulty".[2] The use of examples tends to lower the standard to that of a balance of probabilities and encourage a subjective standard.[3]

By giving illustrations it risks creating the impression that the decision "can be made on the same basis as would any decision made in the course of their daily routines", which tends to move the standard closer to one of "probability".[4] It also creates excessive subjectivity in interpretation, where consideration will vary based on each person's life experience.[5]

- ↑ R v Stavroff, 1979 CanLII 52 (SCC), [1980] 1 SCR 411, per McIntyre J (7:0) including p. 416 (SCR)

- ↑

R v Stubbs, 2013 ONCA 514 (CanLII), per Watt JA (3:0) at para 98

R v Bisson, [1998] 1 SCR 306, 1998 CanLII 810 (SCC), per Cory J (7:0) at para 6 ("No matter how carefully they may be crafted, examples of what may constitute proof beyond a reasonable doubt can give rise to difficulties") - ↑ Stubbs, supra at para 99

- ↑

Bisson, supra at para 6

- ↑

Bisson, supra at para 6

Raising a Doubt

A reasonable doubt cannot be based on "speculation or conjecture".[1]

The Crown has no burden to "negativing every conjecture to which circumstantial evidence might be consistent with the innocence of the accused."[2]

"Bero" defence

The absence of evidence due to the police's failure to take investigative steps will sometimes be an important consideration in whether the Crown has proven its case beyond a reasonable doubt.[3]

The defence is permitted to elicit evidence from witnesses of potential inadequacies in the investigation. Oversights in an investigation "can be particularly important where no defence evidence is called."[4]

- ↑

R v Henderson, 2012 NSCA 53 (CanLII), per Saunders JA (3:0) at para 40

R v White, 1994 CanLII 4004 (NS CA), per Chipman JA (3:0)

R v Eastgaard, 2011 ABCA 152 (CanLII), per curiam (2:1) at para 22, aff’d 2012 SCC 11 (CanLII), per McLachlin CJ (7:0)

- ↑

R v Tahirsylaj, 2015 BCCA 7 (CanLII), per Bennett JA (3:0) at para 39

R v Paul (1975), 1975 CanLII 185 (SCC), 27 CCC (2d) 1 (S.C.C.), at 6, (1975), [1977] 1 SCR 181, 64 DLR (3d) 491 (S.C.C.), per Ritchie J (6:3)

- ↑

R v Bero 2000 CanLII 16956 (ON CA), (2000), 151 CCC (3d) 545 (Ont.C.A.), per Doherty JA (3:0) at paras 56 to 58

- ↑

R v Gyimah, 2010 ONSC 4055 (CanLII), per Healey J, at para 20

Bero