Section 487 Search Warrants

| This page was last substantively updated or reviewed January 2023. (Rev. # 92997) |

General Principles

A s. 487 search warrant authorizes, for a limited time, the "search" of a "place" for the purpose of "seizing" a "thing". Once the "things" are seized they are then ordered detained under a s. 490 detention order.

The face of the warrant is what empowers a peace officer to search the identified location for specified evidence.[1]

- Relationship Between the Warrant and the ITO

The Information to Obtain (ITO) is the evidence that gives the issuing justice grounds to grant the order to search. [2] The ITO is not part of the warrant that the authorized officer is expected to examine. They only need to be familiar with the face of the order to understand the scope of the search.[3]

Proper interpretation can be done through the use of the "fellow officer test", which asks whether a fellow officer would understand what is being sought and where the search is permitted based solely on reviewing the face of the warrant.[4]

- Place

A search warrant for a "place" will generally give authority to also search places and receptacles in that place.[5]

- Time

Where not specified on the face of the warrant, all authorizations have the implied requirement that the warrant be executed "within a reasonable amount of time of being issued", which generally expects the same day as issuance.[6]

There is nothing inappropriate with setting an extended window of several days in which the warrant may be executed.[7]

- ↑

R v Townsend, 2017 ONSC 3435 (CanLII), 140 WCB (2d) 240, per Varpio J, at para 53

Re Times Square Book Store and the Queen, 1985 CanLII 170 (ON CA), 21 CCC (3d) 503, per Cory JA

R v Parent, 1989 CanLII 217 (YK CA), 47 CCC (3d) 385, per Locke JA (3:0)

R v Ricciardi, 2017 ONSC 2788 (CanLII), OJ No 2282, per Di Luca J

R v Merritt, 2017 ONSC 80 (CanLII), OJ No 6924, per F Dawson J

- ↑

Townsend, supra, at para 53

- ↑

Townsend, supra, at para 53

- ↑

Townsend, supra, at para 53

R v Rafferty, 2012 ONSC 703 (CanLII), OJ No 2132, per Heeney J, at para 103

- ↑ R v Vu, 2013 SCC 60 (CanLII), [2013] 3 SCR 657, per Cromwell J, at para 39

- ↑ R v Saint, 2017 ONCA 491 (CanLII), per Miller JA re s. 11 CDSA warrants. Note s. 11 does not set out time as an essential element to a search.

- ↑ R v Paris, 2015 ABCA 33 (CanLII), 588 AR 376 re s. 11 CDSA warrant set for 48 hours.

Power to Authorize a Warrant

The section states:

- Information for search warrant

487 (1) A justice who is satisfied by information on oath in Form 1 [forms] that there are reasonable grounds to believe that there is in a building, receptacle or place

- (a) anything on or in respect of which any offence against this Act or any other Act of Parliament has been

or is suspected to have been* committed,- (b) anything that there are reasonable grounds to believe will afford evidence with respect to the commission of an offence, or will reveal the whereabouts of a person who is believed to have committed an offence, against this Act or any other Act of Parliament,

- (c) anything that there are reasonable grounds to believe is intended to be used for the purpose of committing any offence against the person for which a person may be arrested without warrant, or

- (c.1) any offence-related property,

may at any time issue a warrant authorizing a peace officer or a public officer who has been appointed or designated to administer or enforce a federal or provincial law and whose duties include the enforcement of this Act or any other Act of Parliament and who is named in the warrant

- (d) to search the building, receptacle or place for any such thing and to seize it, and

- (e) subject to any other Act of Parliament, to, as soon as practicable, bring the thing seized before, or make a report in respect of it to, a justice in accordance with section 489.1 [restitution of property or report by peace officer].

[omitted (2), (2.1), (2.2), (3), (4)]

R.S., 1985, c. C-46, s. 487; R.S., 1985, c. 27 (1st Supp.), s. 68; 1994, c. 44, s. 36; 1997, c. 18, s. 41, c. 23, s. 12; 1999, c. 5, s. 16; 2008, c. 18, s. 11; 2019, c. 25, s. 191; 2022, c. 17, s. 16.

* [see below re Constitutionality]

[annotation(s) added]

Purpose of Search

The purpose of s. 487 warrants is the "allow the investigators to unearth and preserve as much relevant evidence as possible" by authorizing them "to locate, examine and preserve all the evidence relevant to events which may have given rise to criminal liability."[1]

- ↑ CanadianOxy Chemicals Ltd. v Canada (Attorney General), 1999 CanLII 680 (SCC), [1999] 1 SCR 743, per Major J (7:0), at para 22

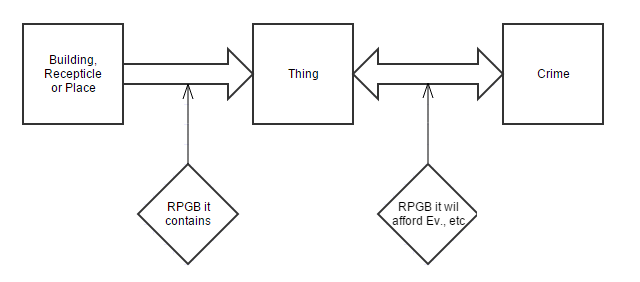

Test to Authorize a Search

Section 487(1) requires that the "justice" be "satisfied by the information on oath" that there are "reasonable grounds to believe" that:[1]

- there is a thing in a "building, receptacle or place";

- the thing is:

- "on or in respect of which any offence against this Act or any other Act of Parliament has been

or is suspected to have beencommitted" (487(1)(a)), - that for which "there are reasonable grounds to believe will afford evidence with respect to the commission of an offence, or will reveal the whereabouts of a person who is believed to have committed an offence, against this Act or any other Act of Parliament,"(487(1)(b))

- that for which "there are reasonable grounds to believe is intended to be used for the purpose of committing any offence against the person for which a person may be arrested without warrant" (487(1)(c))

- "offence-related property" (487(1)(c.1))

- "on or in respect of which any offence against this Act or any other Act of Parliament has been

The four key elements of an ITO for a section 487 warrant should include:[2]

- the place to be searched;

- the items to be searched for;

- what offences these items are evidence of; and

- the time period in which the search is to occur.

A list of requirements of an ITO should include facts establishing grounds of belief for:[3]

- the existence of thing to be searched for;

- the location of the thing to be searched for;

- the location of search is a building, receptacle or place;

- the building, receptacle or place is present at location;

- the offence alleged has been (or suspected of being) committed as described; and

- the thing to be searched for affords evidence of the commission of the offence or possession of the thing is an offence itself.

The evidence within the ITO must permit the officer to form reasonable and probable grounds. The affiant must specify their reasonable grounds within the ITO.

- Outside of Criminal Code

The warrant provisions of the Criminal Code also applies to all other federal statutes even those with search provisions. [4]

A warrant under section 486(1)(b) cannot authorize the search and seizure of "things... that are being sought as evidence in respect of the commission, suspected commission or intended commission of an offence..."[5]

Medical staff who inform the police of the existence of a blood sample taken from the suspect patient is not violating confidentiality of medical records.[6]

- "Justice"

A "justice" is defined in s. 2 of the Code as referring to provincial court level judges.[7]

- Severance of Words

Where words or phrases are superfluous or invalid, the reviewing judge may generally sever that text from the warrant.[8]

- ↑

see also R v Ha, 2009 ONCA 340 (CanLII), 245 CCC (3d) 546, per MacPherson JA

R v Canadian Broadcasting Corp. v Lessard, 1991 CanLII 49 (SCC), [1991] 3 SCR 421 - ↑

R v Richards, 2019 ONSC 3306 (CanLII), per Ducharme J, at para 14

- ↑

R v Chhan, 1996 CanLII 7025 (SK QB), 142 Sask R 232, per Laing J - lists 5 requirements

R v Turcotte, 1987 CanLII 984 (SK CA), 39 CCC (3d) 193, per Vancise JA, at p. 14

R v Adams, 2004 CanLII 12093 (NL PC), NJ No 105, per Gorman J, at para 24

- ↑ R v Multiform Manufacturing Co., 1990 CanLII 79 (SCC), [1990] 2 SCR 624, per Lamer J

- ↑ R v Branton, 2001 CanLII 8535 (ON CA), 154 CCC (3d) 139, per Weiler JA, at para 35

- ↑ R v Decap, 2003 SKQB 301 (CanLII), 237 Sask R 135, per Barclay J

- ↑ Definition of Judicial Officers and Offices

- ↑

R v Nguyen, 2017 ONSC 1341 (CanLII), 139 WCB (2d) 27, per Fairburn J, at para 116

R v Grabowski, 1985 CanLII 13 (SCC), [1985] 2 SCR 434, per Chouinard J

R v Sonne, 2012 ONSC 584 (CanLII), 104 WCB (2d) 876, per Spies J

"Building, Receptacle or Place" to be Searched

Section 487 permits the search of "a building, receptacle or place".

The meaning of "place" is primarily treated as a territorial concept rather than an informational one.[1]

- Motor Vehicles

The motor vehicle can be the thing to be searched for or the place to be searched, depending on the circumstances. Where it is the thing to be searched for, it can be seized by police and then subject to any examinations necessary. Where it is the place to be searched, it must be returned to the older immediately on completion of the search.[2]

- ↑ R v Marakah, 2017 SCC 59 (CanLII), [2017] 2 SCR 608, per McLachlin CJ (“The factor of ‘place’ was largely developed in the context of territorial privacy interests, and digital subject matter, such as an electronic conversation, does not fit easily within the strictures set out by the jurisprudence.”)

- ↑ R v Rafferty, 2012 ONSC 703 (CanLII), OJ No 2132, per Heeney J, at para 48

"Thing" to be Searched For

A search warrant can only be used to seize tangible objects. This means that intangibles, such as money, are not applicable.[1]

- Computer Devices

A computer can be a "thing" and not a "place" within the meaning of s. 487.[2] This is generally since a "thing" is generally a corporeal object and the data on the machine does not meet that definition. The computer, once seized, can be examined pursuant to police access rights to items held under s. 490.

- Articles Worn by Person

Such a warrant, however, cannot be used to search a person or seize anything on a person.[3]

- Finger Prints

Finger prints cannot be taken with a 487 warrant.[4]

- Foreign Objects Found inside a Person

A bullet found inside an accused person cannot be included.[5]

- DNA on Bandages

A standard warrant may be used to seize a disposed bandage in order to perform a DNA test on it. DNA warrant is not necessary.[6] However, where the bandage is still being worn at the time there is a suggestion that a 487 warrant would not be valid and a DNA warrant would be the correct route.[7]

- Blood Vials

A warrant may be used to seize blood vials taken from the accused. There is no need to exhaust other options such as making a blood demand first.[8]

- Motor Vehicles

The motor vehicle can be the thing to be searched for or the place to be searched, depending on the circumstances. Where it is the thing to be searched for, it can be seized by police and then subject to any examinations necessary. Where it is the place to be searched, it must be returned to the older immediately on completion of the search.[9]

- Basket Clauses

The language of the warrant should be as specific as possible. It is undesirable to include phrases such as "and other relevant things."[10] Use of "basket clauses" may be treated as redundant and will be severed from the text.[11] The main determiner is whether the clause makes the descriptions of the things too "vague, overboard and lacking in certainty".[12]

- Level of Detail

While previously necessary, there is no need for the affiant to describe the items in "scrupulous exactitude".[13]

- ↑ R v Bank du Royal Du Canada, 1985 CanLII 3629 (QC CA), 18 CCC (3d) 98, per Kaufman JA

- ↑

R v Barwell, [2013] OJ No 3743 (C.J.)(*no CanLII links)

, per Paciocco J

R v Weir, 2001 ABCA 181 (CanLII), 156 CCC (3d) 188, per curiam (3:0), at para 19

R v Fedan, 2016 BCCA 26 (CanLII), 89 MVR (6th) 188, per Smith JA (3:0), at para 73 - airbag data recorder

cf. R v KZ, 2014 ABQB 235 (CanLII), 589 AR 21, per Hughes J

- ↑ R v Legere, 1988 CanLII 129 (NB CA), 43 CCC (3d) 502, per Angers JA (3:0)

- ↑ R c Bourque, 1995 CanLII 4764 (QC CA), per Tourigny JA (3:0)

- ↑ R v Laporte, 1972 CanLII 1209 (QC CS), (1972) 8 CCC (2d) 343, per Hugessen J

- ↑

R v Kaba, 2008 QCCA 116 (CanLII), per Doyon JA (3:0), at para 32

- ↑

R v Miller, 1987 CanLII 4416 (ON CA), 62 OR (2d) 97, 38 CCC (3d) 252, per Goodman JA - bandage not permitted while person is wearing it

- ↑ R v O’Brien, 2007 ONCA 138 (CanLII), 2005 CarswellOnt 10009, per curiam (3:0)

- ↑ R v Rafferty, 2012 ONSC 703 (CanLII), OJ No 2132, per Heeney J, at para 48

- ↑

R v JEB, 1989 CanLII 1495 (NS CA), 523 CCC (3d) 224, per Macdonald JA re "other sexual aids" clause

- ↑ R v WCS, 2000 CanLII 28289 (NS SC), 581 APR 52, per Saunders J, at para 56

- ↑ Church of Scientology and The Queen (No. 6), Re, 1987 CanLII 122 (ON CA), 31 CCC (3d) 449, per curiam

- ↑

Church of Scientology, ibid.

R v Nguyen, 2017 ONSC 1341 (CanLII), 139 WCB (2d) 27, per Fairburn J

BGI Atlantic Inc v Canada (Minister of Fisheries & Oceans), 2004 NLSCTD 165 (CanLII), 717 APR 206, per LeBlanc J

R v Rollins, 1991 CanLII 490 (BC SC), per MacKinnon J

Relationship Between "Thing" and Offence

Section 487 sets out four types of relationships between the thing to be searched for and seized and the offence investigated. They are:

- "anything on or in respect of which an offence ... has been ... committed" (s. 487(1)(a))

- "anything that there are reasonable grounds to believe will afford evidence with respect to the commission of an offence, or will reveal the whereabouts of a person who is believed to have committed an offence..." (s. 487(1)(b))

- "anything that there are reasonable grounds to believe is intended to be used for the purpose of committing any offence against the person for which a person may be arrested without warrant" (s. 487(1)(c))

- "any offence-related property" (s. 487(1)(c.1))

- Constitutionality

The clause "suspected to have been" made in s. 487(1)(a) is likely to be found unconstitutional and should be read out of the section.[1]

- ↑

See also R v Fedossenko, 2013 ABCA 164 (CanLII), at paras 19 to 20

R v Chabinka, 2009 ONCJ 175 (CanLII), at paras 34 to 44

"Will Afford Evidence"

The phrase "will afford evidence" is treated as interchangable with "may be obtained", "could be obtained", "will be obtained", and "may afford evidence". They all will require "credibility based probability" that the thing sought will be found.[1]

- ↑

R v Brand and Ford, 2006 BCSC 305 (CanLII), 216 CCC (3d) 65, per Blair J, at paras 28, 32 to 33

Power to Order

Section 487(1) permits the justice, once satisfied he is able to authorize a search warrant, may order a "peace officer" to "search the building, receptacle or place for any such thing and to seize it", and, "as soon as practicable, bring the thing seized before, or make a report in respect thereof to, the justice".

Content of the 487 Warrant

The body of the warrant must meet several requirements to be facially valid. There must be:[1]

- an authorized officer;

- an authorized device, investigative technique, procedure, or act; and

- private property to be searched or seized.

The sufficiency of the description of the place must be assessed based on the face of the warrant, separately from the contents of the ITO or the manner it was executed.[2] Failure to name a place on the warrant "is not a mere matter of procedural defect, but so fundamental as to render the document of no legal effect."[3]

There is no need to specify the identity of the suspect, and simply refer to them as "persons unknown."[4]

- Forms

Section 487(3) requires that Form 5 be used in a search warrant:

487

[omitted (1), (2), (2.1) and (2.2)]

- Form

(3) A search warrant issued under this section may be in the form set out as Form 5 [forms] in Part XXVIII [Pt. XXVIII – Miscellaneous (ss. 841 to 849)], varied to suit the case.

(4) [Repealed, 2019, c. 25, s. 191]

R.S., 1985, c. C-46, s. 487; R.S., 1985, c. 27 (1st Supp.), s. 68; 1994, c. 44, s. 36; 1997, c. 18, s. 41, c. 23, s. 12; 1999, c. 5, s. 16; 2008, c. 18, s. 11; 2019, c. 25, s. 191; 2022, c. 17, s. 16.

[annotation(s) added]

- ↑ see the language of s. 487.01

- ↑ R v Parent, 1989 CanLII 217 (YK CA), 47 CCC (3d) 385, per Locke JA (3:0) - no address whatsoever on warrant, but address present in ITO

- ↑ Parent

- ↑ R v Sanchez, 1994 CanLII 5271 (ON SC), 93 CCC (3d) 357, per Hill J

Name of Authorized Officer

A warrant under 487 and 487.1 need not state in the body of the warrant the identity of the officer authorized to execute the search. Failure to do so will not be fatal.[1]

- ↑

{R v Lucas, 2009 CanLII 43418 (ONSC), [2009] OJ No 5333 (Ont Sup Ct J), per Nordheimer J, at paras 9 to 12

R v Benz, 1986 CanLII 4641 (ON CA), 27 CCC (3d) 454, per MacKinnon ACJO

R v KZ, 2014 ABQB 235 (CanLII), 589 AR 21, per Hughes J

Description of Premises to be Searched

A search warrant must specify the premises that is to be searched.[1]

An "adequate" description of the place to be searched is a "fundamental component" to the authorization.[2]

There must be enough information that the authorizing justice is assured they are not granting "too broad" an authorization or one that is "without proper reason".[3]

An authorization that is not "adequate" in invalid.[4] What is "adequate" will vary on the case and circumstances.[5]

For a multi-unit building, it is not enough to simply provide an address. There must be specific information on the location within the building.[6]

A warrant of a premises must accurately describe the location to be searched. If it fails to do so the warrant will be invalid.[7]

- Wrong Address

If the address in the warrant is wrong, the search becomes warrantless.[8]

It is not possible to amend a warrant once granted.[9]

See also: Information to Obtain a Search Warrant#Error in Address

- ↑

s. 487(1)

McGregor and The Queen, Re, 1985 CanLII 3539 (MB QB), 23 CCC (3d) 266, per Oliphant J - ↑ R v Ting, 2016 ONCA (CanLII), 333 CCC (3d) 516, per Miller JA

- ↑ Ting, ibid.

- ↑ Ting, ibid.

- ↑ Ting, ibid. ("Just what constitutes an adequate description will vary with the location to be searched and the circumstances of each case.")

- ↑ Ting, ibid. ("With respect to a multi-unit, multi-use building, as seen in this case, it is not enough to simply provide a street address that distinguishes the building from others. The description must adequately differentiate the units within the building, as those in a multi-unit dwelling have the same expectation of privacy as those in a single-unit dwelling.")

- ↑ R v Re McAvoy (1970), 12 CRNS 56 (NWTSC)(*no CanLII links) , at para 57 ("To avoid search warrants becoming an instrument of abuse it has long been understood that if a search warrant ... fails to accurately describe the premises to be searched ... then it will be invalid")

- ↑

see R v Krammer, 2001 BCSC 1205 (CanLII), [2001] BCJ No 2869 (S.C.), per McEwan J

R v Silvestrone, 1991 CanLII 5759 , per Toy JA (2:1), at pp. 130-132 - ↑

Sieger v Barker, 1982 CanLII 634 (BC SC), 65 CCC (2d) 449, per McEachern CJ

R v Jamieson, 1989 CanLII 202 (NS CA), 48 CCC (3d) 287, per MacDonald JA ("The only recourse had was to apply by an information or oath for a new warrant to search the appellant's residence")

Special Use Cases

It is permissible to use a s. 487 warrant to re-seize things in the custody of police under a s. 490 detention order in order to authorize additional examination.[1]

- Computer Searches

Computers are an exception to the receptacle rule as they are "to a certain extent" a separate place that require a separate authorization.[2] This is because of the high degree of privacy that exists in a home computer and the immense amount of information that they can contain, including information that is automatically generate by the user's activities, and the enduring nature of the data.[3]

A residential warrant that contemplates the seizure of a computer authorizes the police to examine its data.[4]

- Types of Devices to be Searched

Where a warrant authorizes a residential search for documents without mention of whether computers are included, may still permit the officers to search computer equipment so long as they are only searching for the documents authorized by the warrant. No special mention of computers is needed.[5]

- ↑

R v Stillman, 1997 CanLII 384 (SCC), [1997] 1 SCR 607, per Cory J (4:3), at para 128

R v Jones, 2011 ONCA 632 (CanLII), 278 CCC (3d) 157, per Blair JA, at para 36

R v Cole, 2012 SCC 53 (CanLII), [2012] 3 SCR 34, per Fish J, at para 65 ("The police may well have been authorized to take physical control of the laptop and CD temporarily, and for the limited purpose of safeguarding potential evidence of a crime until a search warrant could be obtained. " [emphasis removed])

- ↑

R v Vu, 2013 SCC 60 (CanLII), [2013] 3 SCR 657, per Cromwell J, at paras 39, 46, 47, 51 and 54

- ↑

Vu, ibid., at paras 40 to 43

- ↑

Vu, ibid.

R v Telus Communications Co, 2013 SCC 16 (CanLII), [2013] 2 SCR 3, per Cromwell J (dissenting on another issue)

- ↑ R v Vu, 2011 BCCA 536 (CanLII), 285 CCC (3d) 160, per Frankel JA -- appealed to 2013 SCC 60 (CanLII)

Manner of Search

Searches Intruding on Solicitor-Client Privilege

When searching a lawyer's office, the police have a duty to minimize which requires:[1]

- that a search not be authorized unless there is no other reasonable solution and,

- that the authorization be given in terms that, to the extent possible, limit the impairment of solicitor-client privilege

Where police can anticipate the search of a location where they have reasonable grounds to believe there may be solicitor-client privilege, the warrant and ITO should include special provisions to protect solicitor-client privilege.[2]

Where a warrant authorizes the seizure of "legal correspondence", which is presumptively privileged, the correct procedures requires that the documents be placed under seal and then the applicant must identify the documents which are presumed privileged so that the reviewing judge may determine whether privilege actually exists.[3]

The method of review is a matter of judicial discretion.[4]

- ↑ Maranda v Richer, 2003 SCC 67 (CanLII), [2003] 3 SCR 193, per LeBel J

- ↑

e.g. R v Schultz, 2018 ONCA 598 (CanLII), 142 OR (3d) 128, per Brown JA (3:0), at para 5

- ↑ R v Douglas, 2017 MBCA 63 (CanLII), 10 WWR 446, per Cameron J

- ↑ R v Husky Energy Inc, 2017 SKQB 383 (CanLII), per Kalmakoff J, at para 12

Computer Search

See Also

- Applying for Judicial Authorizations

- Contents of the ITO

- Detention Order for Things Seized Under Section 489 or 487.11

- General Warrants

- ITO Drafting and Search Execution Checklist

- Judicial Authorization Chart

- Search Warrant Evidence

- Judicial Authorization Standard of Review

- Execution of Warrants

- Special Search Issues

- Sealing and Unsealing Warrants

| ||||||||