Acceptance of Evidence

- < Evidence

Introduction

In a criminal hearing, a trier of fact will generally determine facts based solely on admissible evidence given through witnesses, physical exhibits, and admissions by the parties.[1]The adversarial system depends on the production of evidence by parties in order to guarantee "its sufficiency and trustworthiness".[2] It is not for the judges "go looking for evidence" and it is irrelevant that other relevant materials may exist out there that was not adduced.[3]

Evidence provides a means of allowing facts to be proved for the purpose of deciding issues in litigation. The trier of fact may only consider evidence that is admissible, material and relevant. Even then, evidence that creates undue prejudice may nonetheless be ruled inadmissible.

The purpose of the rules of evidence are to permit the trier-of-fact to "get at the truth and properly determine the issues".[4]

- Onus

A judge may only base a decision on "evidence presented at trial, except where judicial notice may be taken" or any other findings permitted under the Code.[5]

The party seeking to tender evidence must meet the necessary threshold requirements of admissibility before it can be considered.[6]

- Requirements Before Acceptance

For a trier-of-fact to receive evidence, the judge must be satisfied that the evidence is:[7]

- relevant,

- material,

- not barred by rules of admissibility, and

- not subject to discretionary exclusion.

Once relevance and materiality is established, the evidence is admissible except where captured by an exclusionary rule.[8]

While the rules of evidence always apply to criminal matters, courts are entitled to be flexible with the evidence rules in order to "prevent miscarriages of justice".[9]

- Objection to Acceptance of Evidence

On application to exclude evidence, counsel should be required to "state with reasonable particularity the grounds upon which the application for exclusion is made".[10]

Barring "unusual and unforeseen circumstances" any objections to the admission of evidence must be "taken before or when that evidence is tendered, not afterwards".[11] Unusual circumstances "do not include previously known yet unpursued Charter applications or a change in counsel".[12]

- Consent to Admit

The existence of consent between the parties to admit evidence will generally the judge to accept the evidence irrespective of its lawful admissibility unless it impacts trial fairness.[13]

- Defence Evidence Favoured

The courts should be reluctant to use exclusionary rules to prevent the accused from adducing evidence as it may support the defence.[14]

- Appellate Review

The admissibility of evidence is a question of law and is reviewable on a standard of correctness.[15] Admission of irrelevant or otherwise inadmissible evidence may be an error of law.[16]

- ↑

R v VHM, 2004 NBCA 72 (CanLII), per Ryan JA citing McWilliams, Canadian Criminal Evidence 4th Ed. (Aurora, Ont. Canada Law Book Inc, 2004 at para 23:10)

- ↑

VHM, ibid.

- ↑ UK: Shortland v Hill & Anor [2017] EW Misc 14 (CC), at para 20

- ↑

R v Seaboyer; R v Gayme, 1991 CanLII 76 (SCC), , [1991] 2 SCR 577, per McLachlin J ("fundamental to our system of justice that the rules of evidence should permit the judge and jury to get at the truth and properly determine the issues."

- ↑

R v Bornyk, 2015 BCCA 28 (CanLII), per Saunders JA, at para 8 - judge improperly relied on academic articles not in evidence

see also R v RSM, 1999 BCCA 218 (CanLII), per Finch JA, at para 20

R v Cloutier, 2011 ONCA 484 (CanLII), per Weiler JA

- ↑

R v Johnson, 2010 ONCA 646 (CanLII), , [2010] OJ No 4153, per Rouleau JA, at para 90

- ↑

R v Candir, 2009 ONCA 915 (CanLII), per Watt JA, at para 46 - requires evidence be (1) relevant (2) material (3) admissible

R v Cyr, 2012 ONCA 919 (CanLII), per Watt JA, at para 96 - sets out the four points of admissibility

see also R v Zeolkowski, 1989 CanLII 72 (CanLII), per Sopinka J

R v Watson, 1996 CanLII 4008 (ON CA), , 108 CCC (3d) 310, (Ont. C.A.), per Doherty JA

- ↑

see Zeolkowski, supra

Watson, ibid. - ↑

R v Muise, 2013 NSSC 141 (CanLII), per Rosinski J, at para 47 aff'd on other grounds 2015 NSCA 54 (CanLII), per Fichaud JA

R v Muise, 2013 NSCA 81 (CanLII), per Hamilton JA, at para 27

R v Howe, 2016 NSSC 140 (CanLII), per Rosinski J, at para 7

- ↑

R v Hamill, 1984 CanLII 39 (BC CA), , [1984] 6 WWR 530, per Esson JA

- ↑

R v Jir, 2010 BCCA 497 (CanLII), per Frankel JA, at para 9

- ↑

Jir, ibid., at para 9

R v Kutynec, 1992 CanLII 7751 (ON CA), per Finlayson JA, at p. 294 (CCC)

R v Bunbury, 2005 YKTC 51 (CanLII), per Ruddy J, at paras 11 to 14

- ↑

R v WJM, 2018 NSCA 54 (CanLII), per Beveridge JA, at paras 34 to 35

- ↑ Seaboyer, supra ("Canadian courts, like courts in most common law jurisdictions, have been extremely cautious in restricting the power of the accused to call evidence in his or her defence, a reluctance founded in the fundamental tenet of our judicial system that an innocent person must not be convicted. It follows from this that the prejudice must substantially outweigh the value of the evidence before a judge can exclude evidence relevant to a defence allowed by law. Exclusionary rules of evidence have been established with a purpose in mind. A trial does not benefit from admitting evidence which is not reliable. Such evidence can mislead the trier of fact. Such evidence can negatively impact upon trial fairness and truth-seeking.")

- ↑

R v Simpson, 1977 CanLII 1142 (ON CA), , (1977), 35 CCC (2d) 337 (Ont. C.A.), per Martin JA

R v Starr, 2000 SCC 40 (CanLII), per Iacobucci J, at para 184

R v Harper, 1982 CanLII 11 (CanLII), per Estey J - ↑ R v Mian, 2012 ABCA 302 (CanLII), per curiam, at para 39 appealed on other grounds at 2014 SCC 54 (CanLII)

Relevance

Evidence must be relevant before it can be admissible, irrelevant evidence must be excluded. [1] Any relevant evidence will be admissible unless otherwise excludable for legal or policy-based reasons.[2]

Relevancy is evidence that tends, "as a matter of logic and human experience", to make a proposition more likely to be true.[3]

Relevancy requires that there be a nexus between facts. The evidence should permit an inference that if one fact exists the other must as well.[4] Relevance is "assessed in the context of the entire case and the positions of counsel. It requires a determination whether, as a matter of human experience and logic, the existence of a particular fact, directly or indirectly, makes the existence or non-existence of a material fact more probable than it would be otherwise".[5]

Certain evidence does not cease to be relevant or become irrelevant simply because it can support more than one inference. [6]

Relevance is sometimes divided into 1) logical relevance and 2) legal relevance.[7] Logical relevance refers to the connection between two facts.

- Logical Relevance

For something to be logically relevant, it is not necessary that the evidence "firmly establish, on any standard, the truth or falsity of a fact in issue".[8] There is no minimum probative value required for evidence to be relevant.[9]

- Legal Relevance

Legal relevance is the cost/benefit analysis of the admission of evidence on the basis of: [10]

- the probative value outweighing prejudicial effect;

- the "inordinate amount of time which is not commensurate with its value"; and

- the evidence's "misleading" effect is "out of proportion to its reliability".

All relevant evidence is admissible exception for the discretionary power of the judge to exclude evidence that is unduly prejudicial, misleading, or confusing.[11]

- Multi-count indictments

Where the accused is charged with multiple counts. The admissibility of evidence towards one count does not mean that it is admissible against other counts.[12]

- Appellate Review

The relevance of evidence is a question of law and is reviewable on a standard of correctness.[13]

- Constitution

It has been suggested that the admission of irrelevant evidence is contrary to the principles of fundamental justice found in s. 7 of the Charter.[14]

- ↑

Hollington v Hewthorn & Co. Ltd., [1943] K.B. 587 (C.A.), at p. 594 (“all evidence that is relevant to an issue is admissible, while all that is irrelevant is excluded”)

R v R v Cloutier, 1979 CanLII 25 (SCC), , (1979), 48 CCC (2d) 1 (SCC), per Pratte J

R v Zeolkowski, 1989 CanLII 72 (SCC), , [1989] 1 SCR 1378, 50 CCC (3d) 566, per Sopinka J

- ↑

R v Morris, 1983 CanLII 28 (CanLII), per Lamer J, at p. 201

R v Headley, 2018 ONSC 5818 (CanLII), per Barnes J, at para 6

- ↑

R v J-LJ, 2000 SCC 51 (CanLII), per Binnie J ("Evidence is relevant “where it has some tendency as a matter of logic and human experience to make the proposition for which it is advanced more likely than that proposition would appear to be in the absence of that evidence” (D. M. Paciocco and L. Stuesser, The Law of Evidence (1996), at p. 19).")

R v Arp, 1998 CanLII 769 (SCC), , [1998] 3 SCR 339 (CanLII), per Cory J

- ↑ Cloutier, supra

- ↑

Cloutier, supra, at p. 27 and referenced in Watt's Manual of Criminal Evidence, 2010, (Thomson Carswell: Toronto, 2008) at Section 3.0

R v Sims, 1994 CanLII 1298 (BC CA), per Wood JA, at pp. 420-27 - relevance determined by the context of the entire case and taking into account Crown and defence

- ↑ R v Underwood, 2002 ABCA 310 (CanLII), per Conrad JA, at para 25

- ↑ R v Mohan, 1994 CanLII 80 (CanLII), per Sopinka J

- ↑ R v Arp, 1998 CanLII 769 (SCC), , [1998] 3 SCR 339, per Cory J, at para 38

- ↑ Arp, ibid., at para 38 ("...there is no minimum probative value required for evidence to be relevant.")

- ↑

Mohan, ibid.

R v Morris, 1983 CanLII 28 (CanLII), per McIntyre J - discusses requirement of "logically probative" evidence - ↑

R v Corbett, 1988 CanLII 80 (SCC), , [1988] 1 SCR 670, (1988), 41 CCC (3d) 385, per Dickson CJ

Morris, supra

See also Discretionary Exclusion of Evidence - ↑

R v Headly, 2018 ONSC 5818 (CanLII), per Barnes J, at para 6

R v Brown, 2007 ONCA 71 (CanLII), , 216 CCC (3d) 299, per Cronk J, at para 13

R v F, 2006 NSCA 42 (CanLII), , 212 CCC (3d) 134, per Cromwell JA, at para 26

See also Similar Fact Evidence - ↑ Mohan, supra, at para 18

- ↑

R v Hewitt, 1986 CanLII 4716 (MB CA), per Huband JA ("The admission of irrelevant and prejudicial evidence by virtue of s. 317(1) is surely contrary to the principles of fundamental justice. ")

R v Guyett, 1989 CanLII 7202 (ON CA), per Brooke JA("It is sufficient to say that I agree with the judgment of the majority in Hewitt that s. 317 goes much farther than the general rules of admissibility and that under it, evidence of bad character can be introduced even if it shows nothing more. To this extent, the section violates the principles of fundamental justice and the guarantee in s. 7 of the Charter. In my opinion, this section cannot be read down.")

Materiality

Evidence must be material to be admissible. Material evidence refers to evidence that contributes to proving a fact that is of consequence to the trial. That is, there must be a relationship between the evidence and a legal issue put to the court.[1] Material evidence can include not only evidence establishing a fact that is necessary to prove an essential element of the case or it can be a fact that refutes or negates an essential element or any other relevant evidence.

This should be treated separately from the question of admissibility and relevance.[2]

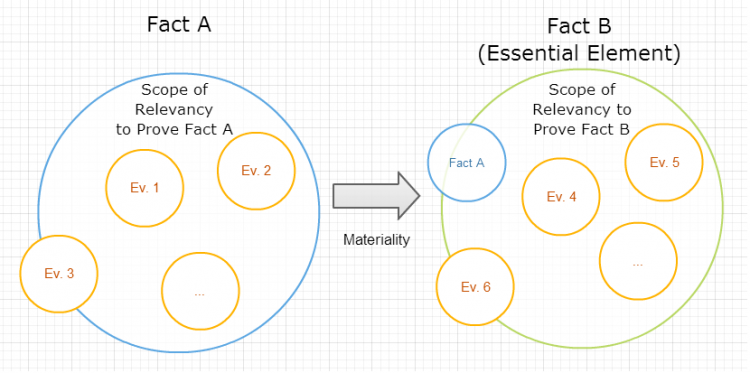

As this diagram shows, materiality represents the proximity of a fact to an essential element to be proven as part of the Crown's case. Fact A is material where it supports some Fact B that, if made out, establishes some legal requirement at issue.

- Relevancy Limited by Materiality

Relevancy can be chained together establishing a link between several propositions, but they must always link back to establishing or negating a material issue.

- ↑

R v Gill, 1987 CanLII 6779 (MB CA), (1987) 39 CCC (3d) 506 (MBCA), per Huband JA

R v Bernardi, 1974 CanLII 1488 (ON CA), (1974), 20 CCC (2d) 523 (ONCA), per Arnup JA - ↑ Bernardi, supra, leave to SCC refused

Rules of Admissibility

Courts must only consider admissible evidence.[1] Where evidence is relevant and material the evidence should be admitted unless their exclusion is justified.[2]

Real evidence that has been proven to be relevant and material are prima facie admissible regardless of whether the investigative conduct to seize the evidence was lawful or not.[3]

Much of the entirety of the rules of evidence concerns the question of what is admissible evidence. As such, admissibility of evidence can be better understood as evidence that is not prohibited by exclusionary rules. Frequently encountered rules of exclusion include:

- Witness competence

- Hearsay

- Opinion

- Character

- Conduct on occasions separate from the offence

- Illegally obtained evidence

- ↑

See also R v Zeolkowski, 1987 CanLII 6836 (MB CA), (1987) 333 CCC 231, per Philp JA

R v Hawkes, 1915 CanLII 347 (AB CA), , (1915) 25 CCC 29 (ABCA), per Stuart J - ↑

R v FFB, 1993 CanLII 167 (SCC), , [1993] 1 SCR 697 (CanLII), per Lamer CJ and Iacobucci J, at #par136 para 136 ("The basic rule in Canada is that all relevant evidence is admissible unless it is barred by a specific exclusionary rule.")

R v Collins, 2001 CanLII 24124 (ON CA), per Charron JA, at paras 18 to 19

R v Cyr, 2012 ONCA 919 (CanLII), per Watt JA, at para 116

R v Morris, 1983 CanLII 28 (CanLII), per McIntyre J - adopting Thayer's approach to the admission of evidence - ↑ R v Sadikov, 2014 ONCA 72 (CanLII), per Watt JA, at para 34

Discretionary Exclusion of Evidence

In addition to the application of specific rules exclusionary rules of evidence, there is a residual common law discretion to exclude any evidence where the prejudicial effect of the evidence outweighs the probative value.

Procedure

Whenever evidence is tendered, a judge may ask counsel for the purpose of tendering the evidence and counsel should give a response.[1]

- ↑ Cox, Criminal Evidence Handbook, 2nd edition, at p. 4