Preliminary Inquiry

| This page was last substantively updated or reviewed January 2022. (Rev. # 95884) |

General Principles

The preliminary inquiry justice derives all of its authority from Part XVIII of the Code. [1]

- Inquiry by justice

535 If an accused who is charged with an indictable offence that is punishable by 14 years or more of imprisonment is before a justice and a request has been made for a preliminary inquiry under subsection 536(4) [request for preliminary inquiry] or 536.1(3) [request for preliminary inquiry – Nunavut], the justice shall, in accordance with this Part [Pt. XVIII – Procedure on Preliminary Inquiry (ss. 535 to 551)], inquire into the charge and any other indictable offence, in respect of the same transaction, founded on the facts that are disclosed by the evidence taken in accordance with this Part [Pt. XVIII – Procedure on Preliminary Inquiry (ss. 535 to 551)].

R.S., 1985, c. C-46, s. 535; R.S., 1985, c. 27 (1st Supp.), s. 96; 2002, c. 13, s. 24; 2019, c. 25, s. 238.

[annotation(s) added]

The powers of a preliminary inquiry judge exist only in statute and within Part XVIII of the Code.[2]

- ↑ R v Hynes, 2001 SCC 82 (CanLII), [2001] 3 SCR 623, 159 CCC (3d) 359, per McLachlin CJ

- ↑

Hynes, supra, at para 28

Availability

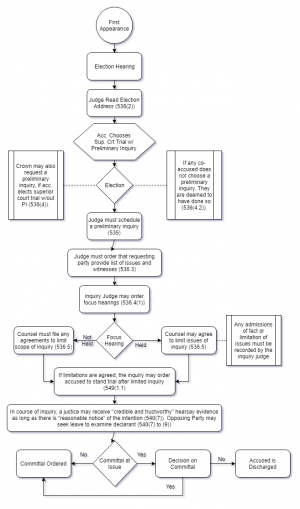

Where an election for trial by superior court judge (alone or with jury) and the maximum penalty is 14 year or more, the provincial court judge receiving the election must inquire whether the accused wishes to have a preliminary inquiry.[1] Where a preliminary inquiry is requested, the provincial court judge has jurisdiction to take evidence as a preliminary inquiry judge.[2]

- Dangerous Offender Application

Where the Crown provides proper notice of an intention to seek a Dangerous Offender Order prior to election and plea on an offence with a penalty under 14 years. The prospects of a Dangerous Offender Order does not create .[3]

- Retrospectivity of Bill C-75 Changes

On September 19, 2019, Bill C-75 removed the availability of preliminary inquiries to offences with maximum penalty of 10 years or less.

There is a division in the case law of whether the amendments in Bill C-75 removing the preliminary inquiry for certain offences will affect those matters with inquiries already scheduled.[4]

Offences that had a maximum penalty of 10 years at the time they were permitted but have since been increased to 14 years or more are not entitled to a preliminary inquiry under the current law. [5]

- ↑ see s. 535

- ↑ see s. 535

- ↑ R v Windebank, 2021 ONCA 157 (CanLII), per Nordheimer JA

- ↑

Not Retro.:

R v RS, 2019 ONCA 906 (CanLII), OJ No 5773, per Doherty JA

R v Fraser, 2019 ONCJ 652 (CanLII), OJ No 4729, per Konyer J

Retro.: R v Kozak, 2019 ONSC 5979 (CanLII), [2019] OJ No 5307, per Cambpell J

R v Lamoureux, 2019 QCCQ 6616, per Galiatsatos J

- ↑

R v CTB, 2021 NSCA 58 (CanLII), per Van den Eynden JA(complete citation pending)

R v SS, 2021 ONCA 479 (CanLII), per Nordheimer JA(complete citation pending)

Purpose

The purpose of the preliminary inquiry is to determine if there is sufficient evidence to set the matter down for trial before a Justice of the Superior Court.[1] In practice the Inquiry is used to test the strength of the Crown’s case.

Its purpose is also "to protect the accused from a needless, and indeed, improper, exposure to public trial where the enforcement agency is not in possession of evidence to warrant the continuation of the process." [2]

It is an "expeditious charge-screening mechanism"[3]

The inquiry judge has a general power to regulate the inquiry process under s. 537. The judge may require counsel to define the issues for which evidence will be called (see s.536.3), and may further limit the scope of the inquiry under section 536.5 and 549.

There is no constitutional right to a preliminary inquiry. Thus, any deprivation of a preliminary inquiry does not violate any principles of fundamental justice.[4]

- ↑

R v O’Connor, 1995 CanLII 51 (SCC), [1995] 4 SCR 411, per L'Heureux‑Dubé J, at para 134 ("The primary function of the preliminary inquiry...is undoubtedly to ascertain that the Crown has sufficient evidence to commit the accused to trial")

R v Hynes, 2001 SCC 82 (CanLII), [2001] 3 SCR 623, per McLachlin CJ, at paras 30 to 31

R v Coke, [1996] OJ No 808(*no CanLII links) , per Hill J, at paras 8 to 11

R v Deschamplain, 2004 SCC 76 (CanLII), [2004] 3 SCR 601, per Major J

R v MS, 2010 CanLII 61755 (NL PC), per Gorman J, at para 24 - ↑ Skogman v The Queen, 1984 CanLII 22 (SCC), [1984] 2 SCR 93, per Estey J, at p. 105

- ↑ Hynes, supra, at para 48

- ↑ R v SJL, 2009 SCC 14 (CanLII), [2009] 1 SCR 426, per Deschamps J, at para 21

Discovery Function

Prior to the amendments in 2005, it has also been used as a venue for discovery.[1]

Since the passing of the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 2002, c. 13 (Bill C-15A), discovery has lost some relevancy as a purpose of the preliminary inquiry. [2] The discovery purpose is "ancillary" to the main purpose of the hearing.[3]

The discovery function of the preliminary inquiry "does not encompass the right of the accused to call evidence ... which is solely relevant to a proposed application to exclude evidence at trial."[4]

Where the accused is in possession of all disclosure covering the investigation and offence there is some suggestion that the discovery purpose of the preliminary inquiry becomes largely irrelevant.[5]

Discovery function does not impose any obligations upon Crown to call all relevant evidence for trial.[6]

- Cross-examining Warrant Affiant (Dawson Applicantion)

There is some support to allow the accused to cross-examine the affiant during the preliminary inquiry.[7] In Ontario, this requires an application before the preliminary inquiry judge to determine if it is available.

- ↑

R v Skogman, 1984 CanLII 22 (SCC), [1984] 2 SCR 93, per Estey J, at p. 105 (SCR)

("the preliminary hearing has become a forum where the accused is afforded an opportunity to discover and to appreciate the case to be made against him at trial where the requisite evidence is found to be present")

See R v Kasook, 2000 NWTSC 33 (CanLII), 2 WWR 683, per Vertes J, at para 25

- ↑ see R v SJL, 2009 SCC 14 (CanLII), [2009] 1 SCR 426, per Deschamps J, at paras 21 and 23, 24

- ↑

R v Bjelland, 2009 SCC 38 (CanLII), [2009] 2 SCR 651, per Rothstein J, at para 36

SJL, supra, at paras 21 to 24

R v Kushimo, 2015 ONCJ 28 (Ont.C.J.)(*no CanLII links) , at para 18

R v Stinert, 2015 ABPC 4 (CanLII), 604 AR 151, per Rosborough J, at paras 6 to 17

- ↑ R v Cowan, 2015 BCSC 224 (CanLII), per Ross J, at para 96

- ↑

R v Thomas, 2017 BCSC 841 (CanLII), per Baird J, at para 21 ("... I note that Mr. Thomas has had disclosure of the entire Crown case, including the specifics of his arrest. The form of additional Charter discovery that he requested at the preliminary inquiry stage was irrelevant to the primary purpose of that proceeding.")

- ↑

R v Pietruk, 1990 CanLII 6822 (ON SC), 74 OR (2d) 220, per Isaac J - application to compel Crown to call witnesses at preliminary inquiry denied

see also Electing a Preliminary Inquiry

- ↑

R v Dawson, 1998 CanLII 1010 (ON CA), 39 OR (3d) 436, per Carthy JA